American University Business Law Review

%4192+

?

779+ 68/)1+

&e Extension Of &e Arbitral Agreement To Non-

Signatories In Europe: A Uniform Approach?

Eduardo Silva Romero

University of Paris Dauphine+*9'6*47/1:'642+64*+).+68)42

Luis Miguel Velarde Sa%er

9/7/-9+1%+1'6*+"'@+6*+).+68)42

4114;8./7'3*'**/8/43'1;4607'8 .B5*/-/8'1)422437;)1'2+6/)'3+*9'9(16

'684,8.+ 422+6)/'1';422437 /7598+!+74198/43'3*6(/86'8/43422437'3*8.+

38+63'8/43'1';422437

A/768/)1+/7(649-.884=49,46,6++'3*45+3'))+77(=8.+&'7./3-843411+-+4,';4963'17';!+:/+;7'8/-/8'14224372+6/)'3

$3/:+67/8=&'7./3-843411+-+4,';8.'7(++3'))+58+*,46/3)197/43/32+6/)'3$3/:+67/8=97/3+77';!+:/+;(='3'98.46/>+*+*/8464,

/-/8'14224372+6/)'3$3/:+67/8=&'7./3-843411+-+4,';46246+/3,462'8/4351+'7+)438')8 0)1'=;)1'2+6/)'3+*9

!+)422+3*+*/8'8/43

!42+64*9'6*4"/1:''3*"'@+69/7/-9+1%+1'6*+A+<8+37/43,A+6(/86'1-6++2+38#443"/-3'846/+739645+

$3/,4625564').2+6/)'3$3/:+67/8=97/3+77';!+:/+;%414

:'/1'(1+'8.B5*/-/8'1)422437;)1'2+6/)'3+*9'9(16:41/77

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

TO

NON-SIGNATORIES

IN

EUROPE:

A

UNIFORM

APPROACH?

EDUARDO SILVA

ROMERO*

&

LuIs

MIGUEL

VELARDE

SAFFER**

Introdu ction

...............................................................................................

372

II.

The

Law

Applicable

to

the

Arbitral

Agreement

...................................

373

A

.

E

nglan

d

......................................................................................

373

B

. S

w

eden

.......................................................................................

373

C

.

Sw

itzerland

................................................................................

374

D

. S

p

ain

..........................................................................................

3

74

E

.

F

ran

ce

.........................................................................................

374

III.The

Contrasting

Approaches

toward

Implied

Consent

........................

375

A.

England:

very

stringent

approach

towards implied

consent

......

375

1.

O

verview

............................................................................

375

2.

P

articularities

......................................................................

376

B.

Sweden:

Stringent

Approach

toward

Implied

Consent

.............

377

1.

O

verv

iew

.............................................................................

377

2.

P

articularities

......................................................................

378

C.

Switzerland:

Intermediate

Approach

toward

Implied

Consent.

378

1.

O

verv

iew

............................................................................

378

2.

Particularities

......................................................................

379

D.

Spain:

Flexible

Approach

toward

Implied

Consent

..................

380

1.

O

verv iew

.............................................................................

380

2.

P

articularities

......................................................................

381

E.

France:

very

flexible

approach

towards

implied

consent

..........

382

1.

O

verv

iew

.............................................................................

382

2.

Particularities

......................................................................

384

C

onclusion

.................................................................................................

385

*

Partner

at

Dechert

(Paris)

LLP.

Professor

of

International

Law

at

the

University

of

Rosario

in

Bogota,

of

Investment

Arbitration

and

International

Contract

Law

at

Sciences

Po

and

of

International Arbitration

at

the

University

of

Paris-Dauphine.

**

Associate

at

Dechert (Paris)

LLP.

LL.M.

by

Harvard Law

School.

Former

Professor

of

Contract

Law

at

the

Catholic

University

of

Peru

and at the

University

of

the

Pacific.

371

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITY

BUSINESS

LA

wREVIEW

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays,

there

is

no

doubt

that

-

under

certain

circumstances

-

an

arbitral

agreement

can

be

extended

to

non-signatories.

Many

theories

have

been

developed

to

this

effect,

such

as

implicit

consent,

pierce

of

the

corporate

veil, and

incorporation

by reference,

among

others.,

In

the

last

two

or three

decades,

especially

among

international

arbitration

practitioners,

consensus

has

emerged

on the

requirements

to

apply

these

theories.

Most

notably,

there

is

general

agreement

on

the

fact

that

-

all

things

being

equal

-

active

participation

by

a

non-signatory

in

the

negotiation,

execution,

performance

and/or

termination

of

the

contract

containing

an

arbitral

agreement

can

be

taken

as

evidence

of

implied

consent

to

arbitrate.

However,

when

the

theory

is

put

into

practice,

as

commonly

occurs,

dissimilar

approaches

resurge.

This

appears

especially

true

when

looking

at

national

courts'

decisions.

Indeed,

whereas

some

judges

interpret

the

circumstances

that

may reveal

implied

consent

in

a

strict

way,

others

show

a

more

relaxed

approach

and

are

willing

to

find

consent

more

easily.

We

believe

this

is

due, at

least

partially,

to

the

different

stance

taken

by

jurisdictions

(and

thus

judges)

towards

factors

that

may

exercise

great

influence

on

the

final

decision

to

extend

or

not

an

arbitral

agreement,

such

as

good

faith,

the

group

of

companies

doctrine

and

the

avoidance

of

a

denial

of

justice.

In the

pages

that

follow,

after

identifying

the

law

applicable

by default

to

arbitral

agreements

in

a

number

of

European

jurisdictions

(the

"Jurisdictions")

(which,

as

can

be

intuited,

is

also

of

relevance

to

the

final

decision

on

the

extension

of

arbitral

agreements),

we

will then

describe

the

contrasting

approaches

taken

in

these

same

Jurisdictions

towards

the

analysis

of

implied

consent,

emphasizing

-

as

mentioned

above

-

the

different

factors

given

relevance

to in

each

Jurisdiction.

Finally,

we

will

finish

our

analysis

with

some

conclusions.

The

Jurisdictions

covered

in

this

paper

are

England,

Sweden,

Switzerland,

Spain

and

France,

which,

according

to

ICC

statistics,

are

some

of

the

countries

chosen

most

often

as

seat

of

international

arbitration

in

2

Europe.

2

1.

See

generally

Eduardo

Silva

Romero,

El

articulo

14

de

la

nueva

Ley

Peruana

de

Arbitraje:

Reflexiones

sobre

cl

contrato

de

arbitraje

realidad,

l

Revista

del

Circulo

Peruano

de

Arbitraje

53

(2011)

(detailing

anaylsis

of

these

theories).

2.

2015

ICC

Dispute

Resolution

Statistics,

ICC

Dispute

Resolution

Bulletin

2016

No.

1

(2016).

Vol.

5:3

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL AGREEMENT

II.

THE LAW

APPLICABLE

TO

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

The

analysis

of

the

extension

of

the

arbitral

agreement

to

non-

signatories

should

begin

by

identifying

the

law

applicable

to

said

agreement.

When

parties

are

silent

on

that

point,

the

Jurisdictions

adopt

different

approaches

to

determine

this

law:

England

and

Sweden

establish

a

strict

and

clear-cut

procedure

to

determine

the

applicable

law;

Switzerland

and

Spain

provide

the arbitral

tribunal

with discretion

to

determine

the

applicable

law; and

France

does

not require

the

arbitral

tribunal

to

refer

to

any

national

law

when

analyzing

the

validity

and/or

scope

of

an

arbitral

agreement.

How

strict

or

flexible

the approach

to

determining

the

law

applicable

by

default

to

the

arbitral

agreement

is,

and

how

much

discretion

is

given

to

the

arbitral

tribunal

for

this

purpose,

may impact

the

final

decision

on

the

extension

of

the

arbitral

agreement.

For

instance,

a

system

which

does

not

require

referring

to

a

national

law

to

determine

the

scope

of

an

arbitral

agreement

avoids

potential

idiosyncratic

requirements

that

may otherwise

prevent

its

extension

to

non-signatories.

In

the

following

paragraphs,

we

quote

the

relevant

provisions

for

each

of

the

Jurisdictions.

A.

England

In

the

Sulamkrica

case,

the

United

Kingdom

Court

of

Appeals

developed

a

clear-cut,

three

prong

test

to

determine

the law

applicable

to

the

arbitral

agreement.

It

held

that:

[T]he

proper

law

[applicable

to

the

arbitral

agreement]

is

to

be

determined

by

undertaking

a

three-stage

enquiry

into (i)

express

choice,

(ii) implied

choice

and (iii)

closest

and

most

real

connection.

As

a

matter

of

principle,

those

three

stages

ought

to

be

embarked

on

separately

and

in

that

order,

since

any

choice made

by

the

parties

ought

to

be

respected.

3

B.

Sweden

Pursuant

to

Art.

48(1)

of

the

Swedish

Arbitration

Act,

in

the

event

of

a

lack

of

agreement

between

the

parties,

the

law

of

the

country

in

which

the

proceedings

take

place

will

apply

to

the

arbitral

agreement:

Where

an

arbitration

agreement

has

an

international

connection,

the

agreement

shall

be

governed

by

the

law

agreed upon

by

the

parties.

Where

the

parties

have

not

reached

such

an

agreement,

the

arbitration

3.

See

Sulamrrica

Cia.

Nacional

de

Seguros

S.A.

v.

Engenharia

S.A.

[2012]

EWCA

(Civ)

638

[25]

(Eng.)

(emphasis

added).

2016

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITYBUSINESS

LA W

REVIEW

agreement

shall

be

governed

by

the

law

of

the

country

in

which,

by

virtue

of

the

agreement,

the

proceedings

have taken

place

or

shall

take

place.

4

C.

Switzerland

Art.

178(2)

of

the

Swiss

Private

International

Act

adopts

the

principle

of

in

favorem

validitatis,

which provides

that

an

arbitral

agreement

will

be

deemed

valid

as

long

as

it

complies

with

one

of

three

different

laws. The

Swiss

Act provides,

in

relevant

part,

"an

arbitration

agreement

is

valid

if

it

conforms

either

to

the

law

chosen by the parties,

or

to

the

law

governing

the

subject-matter

of

the

dispute,

in

particular

the

main

contract,

or

to

Swiss

law."

5

In

the

words

of

the

Swiss Supreme

Court

in

the

case

of

X

Ltd

v.

Y.

and

Z.

S.p.A:

It

behoves

[the

Arbitral

Tribunal]

to

determine which

parties

are

bound

by

that agreement

and

if

necessary

to

find out

if

one

or

more

third parties

not

designated

there

nonetheless

fall

within

its

purview.

Such

an

issue

of

jurisdiction

ratione

personae, which

relates

to the

merits,

must

be

resolved

on the

basis

of

Art.

178

(2)

P1LA ....

That

provision

recognizes

three alternative

means

in

favorem

validitatis,

without

any

hierarchy

between them,

namely

the law

chosen

by

the

parties,

the

law

governing

the

object

of

the

dispute

(lex

causae)

and

Swiss

law.

6

D.

Spain

Art.

9(6)

of

the

Spanish Arbitration

Act

also

adopts

the

principle

of

in

favorem

validitatis:

6.

In

respect

of

international

arbitration,

the

arbitration

agreement

shall

be

valid

and the

dispute shall

be

capable

of

arbitration

if

it

complies

with

the

requirements

established

by

the

juridical

rules

chosen

by

the

parties

to

govern

the

arbitration

agreement,

or

the

juridical

rules

applicable

to

the

merits

of

the

dispute,

or

Spanish

law.

7

E.

France

As

indicated

above,

French

courts

have taken

a

different

approach.

They

do

not

deem

it

necessary

to

refer

to

any

national

law

to

assess

the

validity

and/or

scope

of

an

arbitral

agreement.

The

arbitral agreement

remains

4.

Article

48(1)

of

the

Swedish

Arbitration

Act

(1999).

5.

Article

178(2)

of

the

Swiss

Federal

Act

on

Private International

Law

(1987).

6.

See

X.

Ltd

v.

Y.

and

Z.

S.p.A,

Bundesgericht

[BGer]

[Federal

Supreme

Court]

Aug. 19,

2008,

No.

4A

128/2008

134

ENTSCHEIDUNGEN

DES

SCHWEIZERISCHEN

BUNDESGERICHTS

[BGE]

III 565

(Switz.)

(emphasis

added).

7.

Article

9(6)

of

the

Spanish

Act

60/2003

of

23

December

2003

Vol.

5:3

2016

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

375

independent

(or

delocalized)

from

the

various

national

laws,

which

might,

in

other

jurisdictions,

apply

to

it.

In

ComitW

Populaire

de

la

MunicipalitW

de

Khoms

El

Mergeb

v.

Dalico Contractors,

the

Cour

de

Cassation

said

that:

[B]y

virtue

of

a

substantive

rule

of

international arbitration,

the

arbitration

agreement

is

legally

independent

of

the

main contract

containing

or

referring

to it, and

the

existence

and

effectiveness

of

the

arbitration

agreement

are

to

be

assessed,

subject

to

the

mandatory

rules

of

French

law

and

international

public

policy,

on the

basis

of

the

parties'

common

intention,

there being

no

need

to

refer

to

any

national

law.

8

Similarly,

French

arbitrator

Yves

Derains

has

said

that

"[t]his

prominent

role

given

to

the

common

intent

of

the

parties

is

part

of

a

substantive

rule

of

French

law

that

French

courts apply

without

any

regard

to

any

national

law

that

might

be

applicable

to

the

arbitration

clause

pursuant

to

a

conflict

of

laws

rule."

9

III.

THE

CONTRASTING

APPROACHES

TOWARD

IMPLIED

CONSENT

We

now turn

to

comment

on the

approach

taken

by

courts

in

the

Jurisdictions

when assessing

whether

implied

consent

exists.

As

will

become

apparent

from

our

analysis,

we

attribute the

courts'

contrasting

approaches

-

at

least

partially

-

to

the

different

stances

taken by

the

Jurisdictions

towards

factors

such

as

good

faith,

the

group

of

companies

doctrine,

and the

avoidance

of

a

denial

of

justice.

This

idea

is

strengthened

by the

fact

that,

with

the

exception

of

England,

all

of

the

Jurisdictions

adopt

a

similar

theoretical

approach

towards implied

consent.

In

some

cases, we

will

also

make reference

to

other

regulations

that

reinforce the

approach

-

whether

strict

or

flexible

-

endorsed by

each

Jurisdiction

on

binding

non-signatories.

10

A.

England.-

very

stringent

approach

towards

implied

consent

1.

Overview

Based

on the

evolution

of

international arbitration

with

regard

to

implied

consent,

England

can

be

considered

a

rare

case.

Indeed,

we

have

not

found

decisions

where

an

English

court

accepted

to

extend

an

arbitral agreement

8. Comitd

Populaire

de

la

Municipalitd

de

Khoms

El

Mergeb

v.

Dalico

Contractors,

Cour

de

cassation

[Cass.]

[supreme

court

for

judicial

matters]

le

civ.,

Dec.

20,

1993,

Bull.

civ.

II,

No. 372

(Fr.)

(emphasis

added).

9.

Yves

Derains,

Is

there

A

Group

of

Companies

Doctrine?,

in

MULTIPARTY

ARBITRATION

131,

135

(Eric

Schwartz

and

Bernard

Hanotiau

eds.,

2010).

10.

See

infra

Section

III.

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITYBUSINESS

LA

WREVIEW

to

non-signatories

based

on

implied

consent

due

in large

part

to

the

fact

that

the

doctrine

of

privity

of

contract

has

been given

high

importance.

For

instance,

in

Arsanovia

Ltd.

&

Ors

v.

Cruz

City

1

Mauritius

Holdings,

the

High

Court

said

that

"English

law

requires

that

an

intention

to

enter

into

an

arbitration

clause

must

be

clearly

shown

and

is

not

readily

inferred.""

1

In

a

similar

vein,

in

the

partial

award

rendered

in

ICC

case

13777,

the

arbitral

tribunal

said

that

"English

law

contains

no

statutory

provisions

empowering

a

Tribunal

to

compel

arbitration

against

an

unwilling

non-

signatory.

'

1

2

This

rationale

was

confirmed

by

the

United

Kingdom

Supreme

Court

when,

in

the

famous

case

-

Dallah

Real

Estate

and

Tourism

Holding

Co.

v.

Pakistan

-

it

had

to

assess

the

extension

of

the

arbitral

agreement

to

Pakistan

under

French

law.

After

explaining

what

the

standard

was,

the

Court

said:

This

then

is

the

test

which

must

be

satisfied

before

the

French

court

will

conclude

that

a

third

person

is

an

unnamed

party

to

an

international

arbitration

agreement.

It

is

difficult

to

conceive

that

any

more

relaxed

test

would

be

consistent

with

justice

and

reasonable

commercial

expectations,

however

international

the

arbitration

or

transnational

the

principles

applied.

1

3

2.

Particularities

The

very

stringent

approach

of

English

courts

is

reinforced

by

two

factors.

First,

the

rejection

of

the

group

of

companies

doctrine

(i.e.,

no

weight

is

given

to

the

fact

that

non-signatories

and

signatories

belong

to

the

same

corporate

group).

14

Second,

the

rejection

of

a

general

principle

of

good

faith.

In

Interfoto

Picture

Library

v

Stilletto,

for

example,

the

United

Kingdom

Court

of

Appeals

said:

In

many

civil

law

systems,

and

perhaps

in

most

legal

systems

outside

the

common

law

world,

the law

of

obligations

recognizes

and

enforces

an

overriding

principle

that

in

making

and carrying

out

contracts

parties

should

act

in

good faith

....

English

law

has,

characteristically,

committed

itself

to

no

such

overriding

principle

but

has

developed

piecemeal

solutions

in

response

to

demonstrated

problems

of

11.

Arsanovia

Ltd.

&

Ors

v.

Cruz City

I

Mauritius

Holdings

[2012]

EWHC

(Comm)

3702

[

35]

(Eng.)

(emphasis

added).

12.

ICC

Case

13777,

partial

award

on

jurisdiction

dated

April

2006.

13.

Dallah

Real

Estate

and

Tourism

Holding

Co. v.

Pakistan

[2010]

UKSC

46

[10]

(Eng.)

(emphasis

added).

14.

Peterson

Farms

Inc.

v.

C&M

Farming

Ltd.

[2004]

EWHC

121

[62]

(Eng.).

Vol.

5:3

2016

THE EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

377

unfairness.

1

5

Based

on the above,

we

can

identify

as

particularities

of

the

English

system:

"

The

adoption

of

a

clear-cut,

three

prong

test,

to

determine

the

law

applicable

by

default

to

arbitral

agreements;

*

The

courts'

very

stringent

approach

towards

the

analysis

of

implied consent

to

arbitrate;

"

The

rejection

of

the

group

of

companies

doctrine;

and

"

The

rejection

of

an

overriding

principle

of

good

faith.

B.

Sweden.-

Stringent

Approach

toward Implied

Consent

1.

Overview

Non-signatories

may

be

bound

by

an

arbitral

agreement based

on

their

behavior.

In

a

recent

case,

Profera

AB

v.

Blomgren,

the

Court

of

Appeal

of

Western

Sweden

found

that negotiations

and

exchange

of

drafts

created

an

oral

arbitral

agreement

binding

upon

the

parties:

The

Court

found

that

the

parties

had

agreed

orally

in

regard

the

main

and

determining

issues

of

the

agreement,

which

was

the

purchase price.

The

parties had thus

entered

into

the

agreement, despite

the

fact

that

some

issues

remained

to

be

agreed

upon.

The

Court

then

considered

whether

the

parties

were

bound

by

the

arbitration

clause

in

the

drafts

exchanged.

The

court found

that

the

parties

were

bound

by

the

arbitration

clause

as

almost

all

of

the

discussed

drafts had

contained arbitration

clauses

that

referred

to

the

Swedish

Arbitration

Act.

Further,

the

Defendant-

Appealed

had

never

specifically

objected

to

or

protested

against,

or

otherwise

demonstrated

its

disagreement

with

the

arbitration

clause.

16

In

general,

Swedish

courts appear

to

have

a

stringent

approach

towards

binding

non-signatories.

In

another

recent

case,

the

Supreme

Court

construed

restrictively

the

reference

made

in

an

arbitration

clause

to

disputes

"arising

out

of

or

in

connection

with"

the

contract

that

contained

it,

concluding

that

disputes

that

arose

out

of

a

related

transaction

(to

said

contract),

and

its

parties,

were

not

bound

by

the

arbitral

agreement.

The

Court

reasoned

that

"[t]he

arbitration

clauses

that

are

relevant

in

the

present

case

do

not

specify

any

legal

relationship

except

the

agreement

that

is

regulated

by

the

respective

contractual

document.

Thus,

the

arbitration

clauses

govern

only

the

rights

and

obligations

that

arise

under

these

15.

Interfoto

Picture Library

Ltd.

v.

Stiletto Visual

Programmes Ltd.

[1989]

QB

433

[439]

(Eng.)

(emphasis

added).

16.

Profera

AB

v.

Blomgren

[HovR]

[Court

of

Appeal]

2008-03-12

p.

1

T

2863-

07 (Swed.)

(emphasis added).

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITY

BUSINESS

LA

wREVIEW

agreements.

17

2.

Particularities

The

group

of

companies

doctrine

is

not

endorsed

in

Sweden.'

8

On

the

other

hand,

in

exceptional

circumstances,

consent

to

arbitrate

may

be

inferred

from

passivity.

In

an

unpublished

decision,

the

Svea

Court

of

Appeal

said

that:

In

this

case, the

court

noted

that

the

party

not

singing

or

wishing

to

be

bound

by

an

arbitration

agreement

has

to

take

active

steps

to

make

his

disagreement

known

to

the

other

party.

Whereas

passivity

normally

would

not

result

in

the

formation

of

a

contract

the

case

should

be

distinguished

when

a

party

should

or

ought

to

realize

that

the

other

party

believes

or

assumes

that

a

binding

agreement

has

been

concluded.

This

was

the case

here.

In

such

a

situation,

which

applies

to the

Profura

case,

there

is

an

obligation

to

inform

the

other

party

that

no

such

agreement

has

been

formed.

1

9

Based

on

the

above,

we

can

identify

as

particularities

of

the

Swedish

system:

"

The

adoption

of

a

clear-cut

rule

to

determine

the

law

applicable

by default

to

arbitral

agreements;

"

The

courts'

stringent

approach

towards

binding

non-signatories;

"

The

rejection

of

the

group

of

companies

doctrine;

and

"

The

acceptance,

in

exceptional

circumstances,

that

consent

can

be

inferred

from

passivity.

C.

Switzerland.

Intermediate

Approach

toward

Implied

Consent

1.

Overview

Non-signatories

may

be

bound by

an

arbitral

agreement

based

on

their

behavior.

Consent

will

be

deemed

to

exist when

the

non-signatory

is

involved

in

the

performance

of

the

contract

that

contains

an

arbitral

agreement.

The

Swiss

Supreme

Court

has said

that

"a

third party

involving

itself

in

the

performance

of

the

contract

containing

the

arbitration

agreement

is

deemed

to

have

adhered

to

the

clause by

conclusive

acts

if

it

is

possible

to

infer

from

its involvement

its

willingness

to

be

bound

by

the

arbitration

17.

Concorp

Scandinavia

v.

Karelkamen

Confectionary

[HD]

[Supreme

Court]

2012-04-05

p.

5

0

5553-09

(Swed.).

18.

Anders

Relden

&

Olga

Nilsson,

INTERNATIONAL

ARBITRATION

IN

SWEDEN:

A

PRACTITIONER'S

GUIDE

67

(UlfFranke,

et

al.

eds., 2013).

19.

Ukraine

v.

Norsk

Hydra

[HovR]

[Court

of

Appeal]

2007-12-17

T

3108-06

(Swed.).

Vol.

5:3

2016

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

379

clause.

,

2

0

The

Supreme

Court

has

added,

however,

that

in case

of

doubt

regarding

the

existence

of

consent,

a

restrictive

interpretation

shall

be

observed:

To

interpret

an

arbitration

agreement,

its

legal

nature

must

be taken

into

account;

in

particular

it

must

be

taken

into

account

that

renouncing

access

to

the

state

court

drastically

limits

legal

recourses.

According

to

the

case

law

of

the

Federal

Tribunal,

such

an

intent

to

renounce

cannot

be

accepted

easily,

therefore

restrictive

interpretation

is

required

in

case

of

doubt.

2

1

In

a

similar

vein,

commentators

have

said

that:

As

a

consequence,

it

is

clear

that

under

Swiss

substantive

law

participation

in

the

performance

of

a

contract

may

result

in

an

extension

of

the

arbitration

agreement

to

a

third

party.

However,

in

order

to

[honor]

the

principle

of

relativity

of

contractual

obligations,

the

requirements

for

such

an

extension

are

rather

strict.

2

2

2.

Particularities

The

group

of

companies

doctrine

is

not

endorsed

in

Switzerland.

23

In

this

regard,

the

Supreme

Court

has

said

that:

The

Group

of

Companies

doctrine

does

not

per

se

justify

extending

an

arbitration

clause

to

another

company

within

the

group.

Unless

there

is

an

independent

and

formally

valid manifestation

of

consent

of

the other

company

of

the

group

to

the

agreement

to

arbitrate,

such

an

extension

will be

granted

only

in

very

particular

circumstances

that

justify

a

bona

•

24

fide

reliance

of

a

party

on

an

appearance

caused

by

the

non-signatory.

However,

Swiss

courts

do

consider

good

faith

when

assessing

the

extension

of

the arbitral

agreement.

In

a

decision

rendered

in

2014,

the

Supreme

Court

held

that

"the

principle

of

good

faith

(Art.

2

CC26)

would

nonetheless

require

the

recognition

of

X

's

right

to

act

against

Y

Group

directly

on the

basis

of

the

arbitration

clauses

contained

in

the

Contracts

in

consideration

of

the

circumstances

of

the

case

at

20.

X.

v.

Y

Engineering

S.p.A.,

Tribunal

Frdrral

[TF]

Apr.

7,

2014,

ATF

4A_450/2014

7

(Switz).

(emphasis

added).

21.

FC

X.

v

Y.,

Tribunal

Fdral

[TF]

Jan.

17,

2013,

4A_244/2012

11

(Switz.)

(emphasis

added).

22.

Thomas

Muller,

Extension

of

Arbitration

Agreements

to

Third

Parties

Under

Swiss

Law,

in

CROSS BORDER

ARBITRATION

HANDBOOK

11

(2010)

(emphasis

added).

23.

Matthias

Scherer,

Introduction

to

the

Case

Law

Section,

27

ASA

Bulletin

488,

494 (2009)

("Under

Swiss

law,

mere

affiliation

to

the

same

group

of

companies

is

not

sufficient

to

extend

an

arbitration

clause

signed

by

a

group

company

to

a

parent

or

sister

company.").

24.

X.

Ltd

v.

Y.

and

Z.

S.p.A,

Bundesgericht

[BGerl

[Federal

Supreme

Court]

Aug.

19,

2008,

No.

4A

128/2008

134

ENTSCHEIDUNGEN

DES

SCHWEIZERISCHEN

BUNDESGERICHTS

[BGE]

III

565

(Switz.)

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITYBUSINESS

LAW

REVIEW

hand.

,

2

5

And

in

another

similar

decision,

the

Supreme

Court

said

that

"[i]t

has

already

been

admitted

that

in

specific

circumstances,

a

certain

behavior

may substitute compliance

with

a

formal

requirement

on

the

basis

of

the

rules

ofgoodfaith.

2

6

"

Based

on

the

above,

we

can

identify

as

particularities

of

the

Swiss

system:

*

The

adoption

of

the

principle

of

in

favorem

validitatis,

which

provides

for

the

application

of

up

to

three

different

laws

to

the

arbitral

agreement

*

The

restrictive

interpretation

given

to

consent

in cases

of

doubt;

*

The

rejection

of

the

group

of

companies

doctrine;

and

"

The

relevance

given

to

the

good

faith

principle.

D.

Spain:

Flexible

Approach

toward Implied

Consent

1.

Overview

Non-signatories

may

be

bound

by

an

arbitral

agreement

based

on

their

behavior.

Consent will

be

deemed

to

exist

when

the

non-signatory

is

directly

implicated

in

the

performance

of

the

contract

that

contains

an

arbitral agreement.

The

Supreme

Court

stated

that

"[a]t

all

times,

we shall

ascertain

that

in

the

instant

case

the

arbitration

agreement

contained

in

the

contract

dated

31

July

1992

entails

its

application

to

the

parties

directly

implicated

in the

performance

of

the

contract.

'

,

2

7

Any

finding

that

consent exists

shall

be

strongly supported.

In

this

regard,

the

Spanish

Superior

Court

has

said

that:

[M]ore

controversial

is

the

problem

of

the

extension

of

the

arbitration

agreement

to

legal and

natural

persons that

have

not

signed

it,

not

only

as

a

result

of

the

requirement

of

consent

for

the

existence

of

the

arbitral

agreement

(art.

9.1

LA)

-

which

does not

exclude

implicit consent,

inferred

from

conduct

-

but

also because,

in

any

case,

inferring

such

will,

when

it

is

not

expressed,

shall

be

strongly

supported

given

its

radical

legal

consequences,

i.e.,

the

waiver

of

the

right

to

access

jurisdiction,

hard

core

-

in

the

words

of

the

Constitutional

Court

-

of

the

25.

X.

v

Y

Engineering

S.p.A.,

Tribunal Federal

[TF]

Apr.

7,

2014,

No.

ATF

4A_450/2014

19

(Switz.)

(emphasis

added).

26.

X.

S.A

v.

Z

Sarl,

Tribunal

Federal

[TF]

Oct.

16,

2013,

ATF

4P

115/2003

16

(Switz.)

(emphasis

added).

27.

Interactive Television,

S.A.

c.

Banco

Bilbao

Vizcaya,

S.A.

y

SATCOM

NEDERLAND

BV,

IGNACIO

SIERRA

GIL

DE

LA

CUESTA,

Case

No. 404/2005,

decision

from

the

Supreme Court

(

1

st

Chamber)

dated

26

May

2005, at

Fundamentos

de

Derecho,

First

Item (emphasis added).

Vol.

5:3

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

right

to

an

effective

access

to

justice.2

8

2.

Particularities

Two

factors

relax

the

apparently stringent

approach

of

Spanish

courts.

First,

according

to

commentators,

the

group

of

companies

doctrine

has

certain

weight

in

Spain.

In the IBA

Spanish

Guide for

2012,

for instance,

it

is

said

that

"[a]rbitration

agreements

may

bind

non-signatories

if

they

have

a

very

close

and

strong

relationship

with

a

signing

party,

or

they

have

played

a

strong

role

in

the

performance

of

the

contract.

29

And

Yves

Derains

adds

that:

On

the

basis

of

the

above,

one

may

be tempted

to

conclude

that

the

group

of

companies doctrine

represented

a

brief

momentum

in

the

evolution

of

the

French

case law

relating

to the

application

of

arbitration

clauses

to

non-signatories.

As

a

matter

of

fact,

this

doctrine

has

been

firmly

excluded

in

other

jurisdictions

with

the

apparent

exception

of

Spain.

3

0

Second,

good

faith

plays

a

very

important

role

in

the courts'

assessment

of

whether

implied

consent

exists.

For

instance,

in case

68/2014,

the

Superior

Court

said:

"[i]n

sum,

as

already

stated,

the

Chamber

understands

that

the

extension

to

DIMA

and

GELESA

of

the

arbitration

agreement

contained

in

the

Shareholders

Agreement

is

a

natural

consequence

of

the

contract,

and

is

consistent

with

a

good

faith

interpretation."

31

Finally,

since

it

points

into

the

same

direction,

it

is

worth

briefly

referring

to

the

rules

-

provided

in

the

Spanish

Arbitration

Act

-

for

arbitrating

in

the

corporate

context.

These

rules

effectively

force

minority

shareholders and

administrators

to

arbitrate their disputes.

Art.

11

(bis)

of

the

Spanish

Arbitration

Act

provides,

in

relevant part,

that:

28.

Dima

Distribuci6n

Integral,

S.A.,

y

Gelesa

Gesti6n Logistica,

S.L.

v.

Logintegral

2000,

S.A.U.,

Jesfis

Maria

Santos

Vijande,

Case

No.

68/2014,

decision

from

de

Superior Court,

Civil

and

Criminal

Chamber, dated

16

December

2014,

at

Fundamentos

de

Derecho,

Fourth

Item (emphasis

added).

29.

IBA

Arbitration

Committee,

Arbitration

Guide:

Spain

7

(March

2012),

http://www.google.com/url?sa--t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=

1

&ved=OahUK

Ewju4Ti-bMAhWGFj4KHYyXD

YQFggfMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2F;

www.iba

net.org%2FDocument%2FDefault.aspx%3FDocumentUid%3DE543

1E65-E56C-

4866-8E48-FF9996CF

1AC5&usg-AFQjCNEqgbsqXwroSDATg2hOq9oMkW-Zw

(emphasis

added).

30.

Derains,

supra

note

9,

at

135

(emphasis

added).

31.

Dima

Distribuci6n

Integral,

S.A.,

y

Gelesa

Gesti6n Logistica,

S.L.

v.

Logintegral

2000,

S.A.U.,

Jests

Maria

Santos

Vijande,

Case

No.

68/2014,

decision

from

de

Superior Court,

Civil

and

Criminal Chamber,

dated

16

December

2014,

at

Fundamentos

de

Derecho,

Fourth

Item

(emphasis

added).

2016

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITYBUSINESS

LA

wREVIEW

2.

The

inclusion

in

the

bylaws

of

an

arbitration

clause

will

require

approval

of,

at

least,

two

thirds

of

the

capital

shareholders.

3.

The

bylaws

may

establish

that

the

challenge

of

corporate

agreements

by

the

shareholders

or

administrators

is

subject

to

the

decision

of

one

or

more

arbitrators

....

32

Furthermore,

in

a

recent

decision,

the

Superior

Court

of

Catalonia

extended

an

arbitral

agreement

(contained

in

the

original

bylaws

of

the

company)

to

shareholders

that

acquired

their

shares

after

the

company's

incorporation.

The

Court

held:

By-laws,

as

a

constitutive

agreement

that

has

its

origin

in

the

will

of

the

company's

founders,

can

contain

an

arbitral

agreement

for

the

resolution

of

corporate

conflicts.

An

arbitral

agreement

is

an

accessorial

rule

to

the

by-laws

and

as

such

is

independent

from

the

founders'

will

and

represents

a

further

corporate

rule

that

binds

-

due

to

its

inscription

in

the

Commercial

Registry

-

not

only its

signatories

but

also

the

present

and

future

shareholders.

3

3

Based

on

the

above,

we

can

identify

as

particularities

of

the

Spanish

system:

"

The

adoption

of

the

principle

of

in

favorem

validitatis,

which

provides

for

the

application

of

up

to

three

different

laws

to

the

arbitral

agreement;

*

The

strong

support

needed

to

justify

any

finding

of

implied

consent;

*

The

importance

given

to

the

group

of

companies

doctrine

and

the

good

faith principle;

and

"

The

innovative

provision

of

the

Spanish

Arbitration

Act

for

arbitrating

in

the

corporate

context.

E.

France:

very

flexible

approach

towards

implied

consent

1.

Overview

Non-signatories

may

be

bound

by

an

arbitral

agreement

based

on

their

behavior.

Whether

or

not

this

is

possible

-

based

on the

particular

circumstances

of

each

case

-

will

depend

on the

common

intention

of

the

parties.

This

common

intention

was

initially

analyzed

by

French

courts

through

a

subjectivist

lens,

but

nowadays

an

objectivist

approach

is

mainly

used.

As

explained

by

Pierre

Mayer:

[i]nitially

there

was

a

certain

insistence

on the

fact

that

when

the

non-

32.

Article

I

l(bis)

of

the

Spanish

Act

60/2003

of

23

December

2003.

33.

Case

No.

9/2014,

decision

from

the

Superior

Court

of

Catalonia

dated

6

February

2014

(RJ

2014,

1987).

This

decision

follows

another

one

rendered

by

the

Supreme

Court

on

9

July

2007

(RJ

2007,

4960)

(emphasis

added).

Vol.

5:3

2016

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL

AGREEMENT

383

signatory

had

participated

in

-

generally

-

the

performance

of

the

contract,

and had

been

aware

of

the

existence

of

the

clause,

it

was

to

be

presumed

that

it

had

accepted

to

be

bound

by

the

clause.

I

would

call

this

the

subjectivist

trend.

But

more

recently

a

more

objectivist

trend

has

surfaced.

3

4

Below

we

briefly

describe

the

subjectivist

and

objectivist

approaches.

Under

the

subjectivist

approach,

implied

consent

exists

when

(i)

the

non-signatory

has

an

active

role

in

the

performance

of

the contract,

and

(ii)

it

is

aware

of

the

existence

of

the

arbitral

agreement

(which

is,

in

principle,

presumed).

In

Socit

Ofer

Brothers

v.

The

Tokyo

Marine

and

Fire

Insurance

Co.,

the

Paris

Court

of

Appeal

said:

Considering

that

the

arbitration

clause

present

in

an

international

contract

has

its

own

validity

and

efficacy,

such

as

to

require

its

extension

to

the

parties

directly

involved

in

the

performance

of

said

contract

provided

their

situation

and

activities

indicate

that

they

were

aware

of

the

existence

and

the

scope

of

such

clause,

which

was

agreed

upon

according

to

the

usages

of

international

commerce.

3

5

Emphasizing

the

requirement

of

awareness,

the Paris

Court

of

Appeal

has

said

that

an

arbitral

tribunal

lacks

jurisdiction

over

third

parties

who

did

not,

and

could

not, know

about

the

existence

of

an

arbitral

agreement.

In

one

such

case,

it

affirmatively

stated

that

"[the

arbitral agreement

was]

manifestly

inapplicable

to

SOLEIL

DE CUBA,

third

party

to

the

contract,

who

could

not

know

about

the

existence

of

said

clause

given

its

confidential

nature."

3

6

Under

the

objectivist

approach,

implied

consent

is

only

assessed

based

on

behavior.

Awareness

as

to

the

existence

and/or

scope

of

an

arbitral

agreement

is

irrelevant.

In

the

Alcatel

case,

the

Cour

de

Cassation

said

that

"[t]he

effects

of

the

international

arbitration

clause

extend

to

parties directly

involved

in

the

performance

of

the

contract

and

the

disputes

that

may

result

from

it."

37

Similarly,

in

the

Kosa

France

case,

the

Paris

Court

of

Appeal

said

that

34.

Pierre

Mayer,

The

Extension

of

the

Arbitration

Clause

to

Non-Si

natories

-

The

Irreconcilable

Positions

of

French

and

English

Courts,

27

AM.

U.

INT'L

L.

REv.

831,

831-32

(2012)

(emphasis

added).

35. Soci&t6

Ofer

Brothers

v.

The

Tokyo Marine

and Fire

Insurance

Co.,

Cour

d'appel

[CA]

[regional

court

of

appeal]

Paris,

civ.,

Feb.

14,

1989

(Fr.)

(emphasis

added).

36.

S.A.

Cubana

de

Aviaci6n

v.

Societ6

Becheret

Thierry

Senechal

Gorrias,

Cour

d'appel

[CA]

[regional

court

of

appeal]

Paris,

civ.,

Oct.

23,

2012, 12/04027

(Fr.)

(emphasis added).

37.

Soci6t6

Alcatel

Bus.

Sys.

v.

Amkor

Tech.,

Cour

de

cassation

[Cass.]

[supreme

court

for

judicial

matters]

le

civ.,

Mar.

27,

2010,

Bill

civ.

II,

No.

129

(Fr.)

(emphasis

added).

AMERICAN

UNIVERSITYBUSINESS

LA

wREVIEW

the

arbitral

agreement

should

be

extended

"to

the

parties

directly

involved

in

the

performance

of

[the]

contract

and

in

the

disputes

that

may

result

from

it."

3

8

2.

Particularities

In

general,

French

courts

have

taken

a

flexible

approach

when

assessing

whether

implied

consent

to

arbitrate

exists.

This

is

clearly

evidenced

by

the

decision

rendered

in

the

famous

Dallah

case

by

the

Paris

Court

of

Appeal

(referenced

below).

This

flexible

approach

is

supported

by

two

factors.

First,

the

endorsement

of

the

group

of

companies

doctrine.

As

explained

by

Yves

Derains,

"the

existence

of

a

group

of

companies

is

a

circumstance

that

plays

an

important

role

in

revealing

the

intent

of

parties.

39

Second,

the

weight

given

to

justice

considerations.

Commenting

on

the

decision

of

the

Paris

Court

of

Appeal

in

the

aforementioned

famous

Dallah

case,

where

a

contract

and

its

concomitant

liability

were

extended

to

Pakistan,

non-signatory

party,

Pierre

Mayer

said

that:

Is

the

French

position

shocking?

At

first

sight

it

is,

since

the

consent

of

the

parties

to

arbitrate

is

the

cornerstone

of

arbitration,

and the

Government

of

Pakistan

had

made

clear

its

intention

not

to be

a

party

to

the

contract

containing

the

arbitration

clause.

However,

the

refusal

to

recognize

the

award

would

have

meant

a

denial

of

justice,

since

the

Trust

had

disappeared

and

there

was

no

other

defendant

against

which

Dallah

could

have

acted

than

the

Government.

4

0

Based

on

the

above,

we

can

identify

as

particularities

of

the

French

approach:

"

There

is

no

need

to

refer

to

a

national

law

to

analyze

the

validity

and/or

scope

of

an

arbitral agreement;

*

The

use

of

a

preeminently

objectivist

approach

when

assessing

whether

implied

consent

exists;

and

"

The

relevance

given

to

the group

of

companies

doctrine

and

justice

considerations.

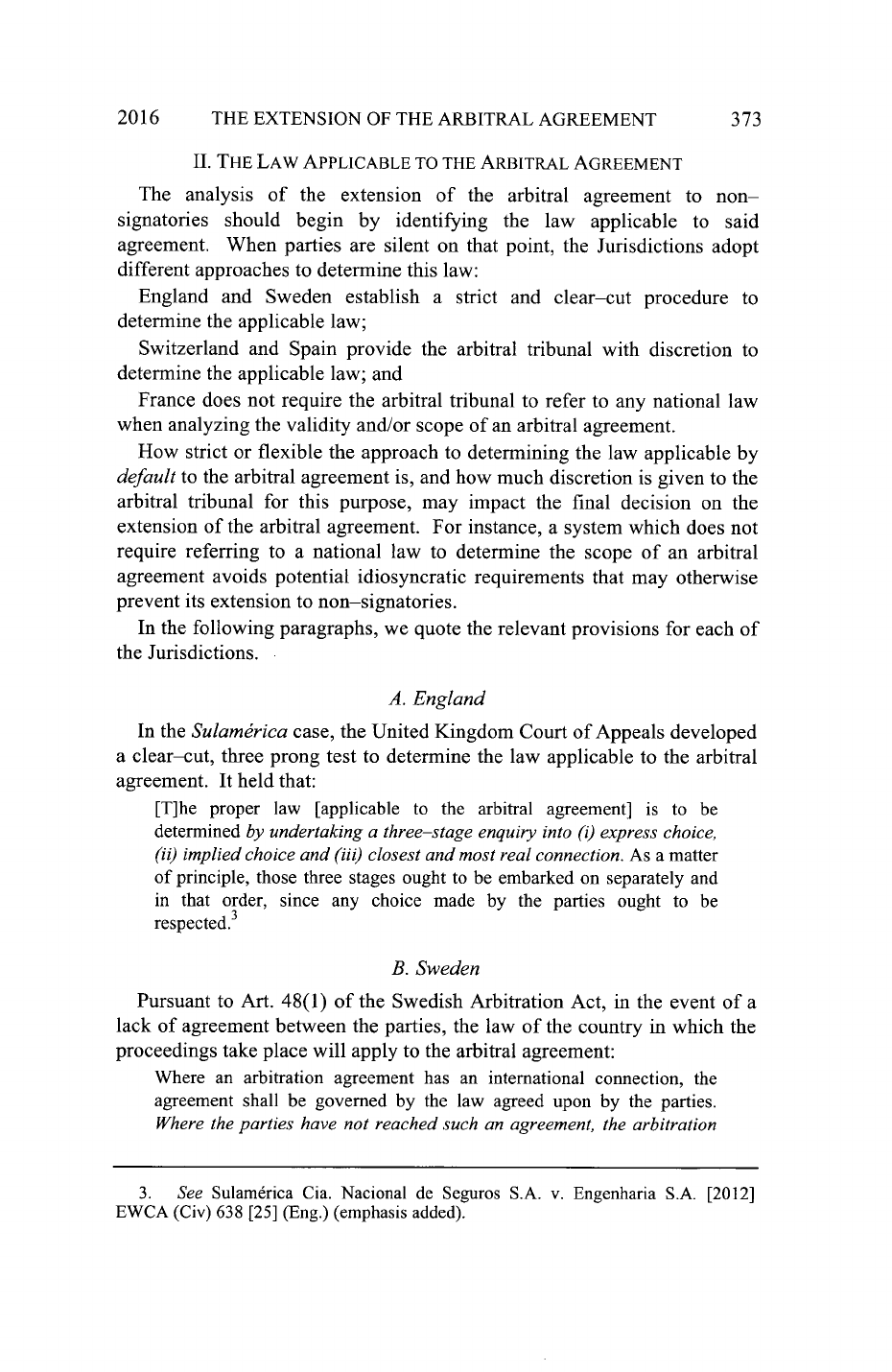

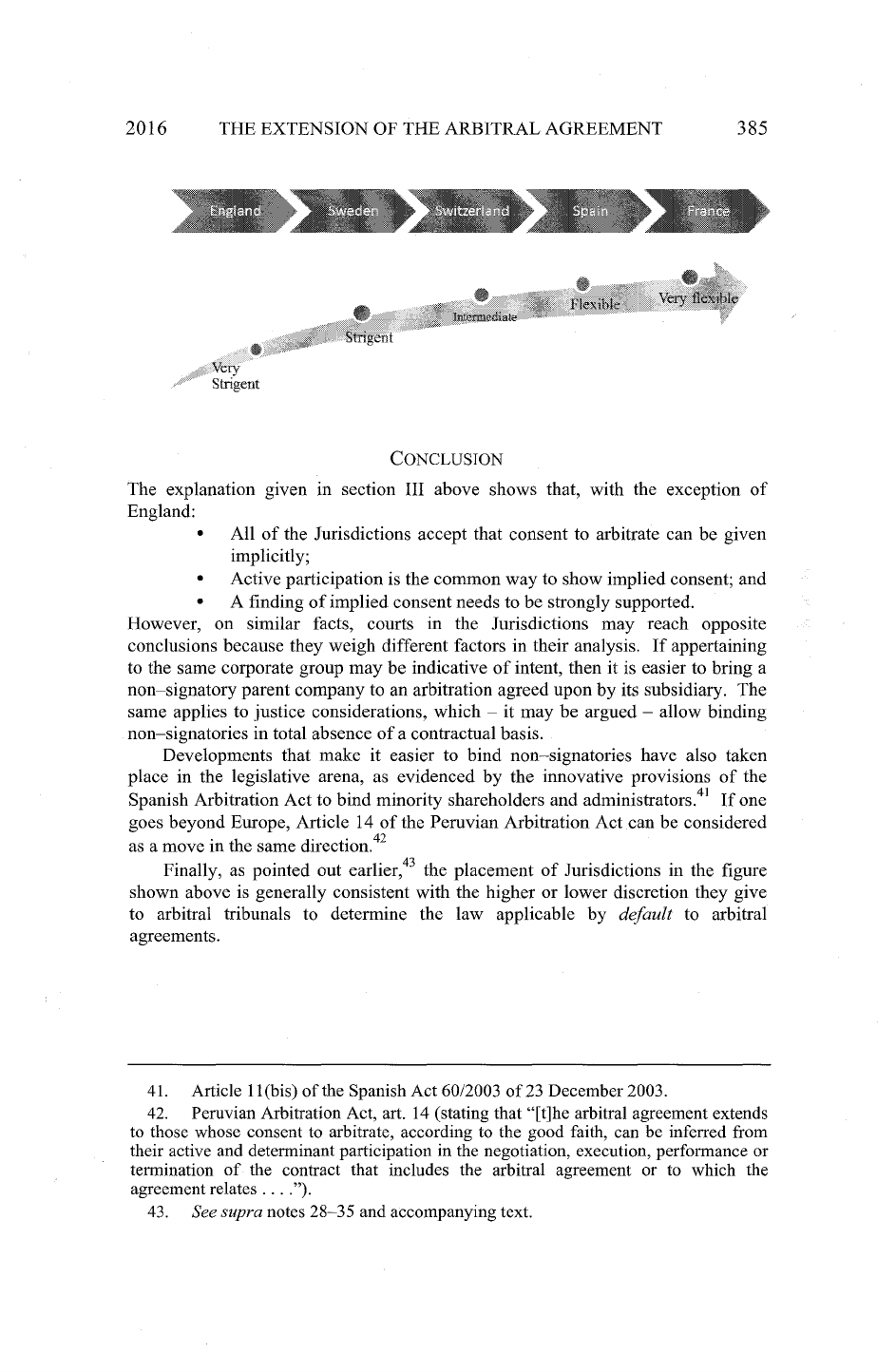

Based

on

what

has

been

said,

the

figure

below

shows

the

placement

of

each

Jurisdiction

in

terms

of

"stringent

approach

v.

flexible

approach"

towards

implied

consent:

38.

Kosa

France

v.

Rhodia

Operations,

Cour

d'appel

[CA]

[regional

court

of

appeal]

Paris,

civ.,

May

5,

2011,

No.

10-04688

(Fr.)

(emphasis

added);

see

also

Amplitude

v.

Promodos,

Cour

de

cassation

[Cass.]

[supreme

court

for

judicial

matters]

le

civ.,

Nov.

7,

2012,

Bill

civ.

II,

No. 11-2589

(Fr.)

(supporting

the

same

approach

as

the

Kosa

France

case).

39.

Derains,

supra

note

9,

at

137

(emphasis

added).

40.

Mayer,

supra

note

34,

at 836

(emphasis

added).

Vol.

5:3

2016

THE

EXTENSION

OF

THE

ARBITRAL AGREEMENT

-;tiigent

:Very

CONCLUSION

The

explanation

given

in

section

III

above shows

that,

with

the

exception

of

England:

* All

of

the

Jurisdictions

accept that

consent

to

arbitrate

can

be given

implicitly;

*

Active

participation

is

the

common

way

to

show

implied

consent;

and

*

A

finding

of

implied consent

needs

to be

strongly

supported.

However,

on

similar

facts,

courts

in

the

Jurisdictions

may

reach

opposite

conclusions because

they

weigh different

factors

in

their

analysis.

If

appertaining

to

the same

corporate

group

may

be

indicative

of

intent,

then

it

is

easier

to

bring

a

non

signatory

parent

company

to

an

arbitration

agreed

upon

by

its

subsidiary.

The

same

applies

to

justice

considerations,

which

it

may

be

argued

-

allow

binding

non-signatories

in

total

absence

of

a

contractual basis.

Developments

that

make

it

easier

to

bind

non-signatories

have

also

taken

place

in

the

legislative

arena,

as

evidenced

by

the

innovative

provisions

of

the

Spanish

Arbitration

Act

to

bind minority

shareholders

and

administrators.

4

'

If

one

goes

beyond

Europe,

Article

14

of

the

Peruvian

Arbitration

Act

can be

considered

as

a

move

in

the

same

direction.

4

2

Finally,

as

pointed

out

earlier,

43

the

placement

of

Jurisdictions

in

the

figure

shown

above

is

generally

consistent with

the

higher

or

lower discretion they

give

to

arbitral

tribunals

to

determine

the

law

applicable

by

default

to

arbitral

agreements.

41.

Article

I1

(bis)

of

the

Spanish Act

60/2003

of

23

December

2003.

42.

Peruvian

Arbitration

Act,

art.

14

(stating

that

"[t]he

arbitral

agreement

extends

to

those

whose consent

to

arbitrate,

according

to

the

good

faith,

can

be

inferred

from

their

active

and

determinant

participation

in the

negotiation,

execution,

performance

or

termination

of

the

contract

that

includes

the

arbitral

agreement or

to

which

the

agreement

relates

.... ").

43.

See

supra

notes

28-35

and

accompanying

text.