124 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

HIT DELETE

THE NEARLY INVISIBLE DESIGN OF THE LAURANCE S. ROCKEFELLER

PRESERVE HINGES ON THE APPROACH HERSHBERGER DESIGN

BROUGHT TO A PROCESS OF ERASURE.

BY PHILIP WALSH

HERSHBERGER DESIGN, LEFT; D. A. HORCHNER, RIGHT

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 125

T

he scars show black against the tender, pale

gray bark of the aspen’s smooth trunk, a

graphic contrast beloved by initial-carving van-

dals. Groups of four jagged lines in roughly

parallel rows rise up the trunk to eight feet or

more above the ground, the calling card not of

restless teenagers, but of the black and grizzly bears

that have visited here. “Check this out,” said Chris

Finlay, the chief of facility management at Grand

Teton National Park, as we paused on the trail

that runs past this tree, mere footsteps from the

interpretive center at the Laurance S. Rockefeller

Preserve. “So these are all hawthorns and choke-

cherries,” Finlay said, sweeping his

arm toward the surrounding thickets

of shrubs, “and the bears, about a

month ago, were thick in here. They

come and just gorge themselves on

the berries during hyperphagia. Now

they’re all gone.”

The berries or the bears? In either

case, I hoped he was right. Finlay

had already lent me a can of “bear

spray,” a red cylinder of compressed

pepper spray the size of a small re

extinguisher. “Keep this accessible.

Don’t bury it in your backpack,” he said. During

the course of my late October visits to the LSR

Preserve, as it is known locally, a can of the spray

was either in the hands or on the belt of every

visitor I encountered. Although the preserve is the

product of meticulous design and construction

on the part of thoughtful human beings, it is also

part of wild nature. This, too, is by design. The

tension between familiarity and risk is a common

theme in the work of the landscape architects at

Hershberger Design, the rm responsible for the

planning and design of the new facility.

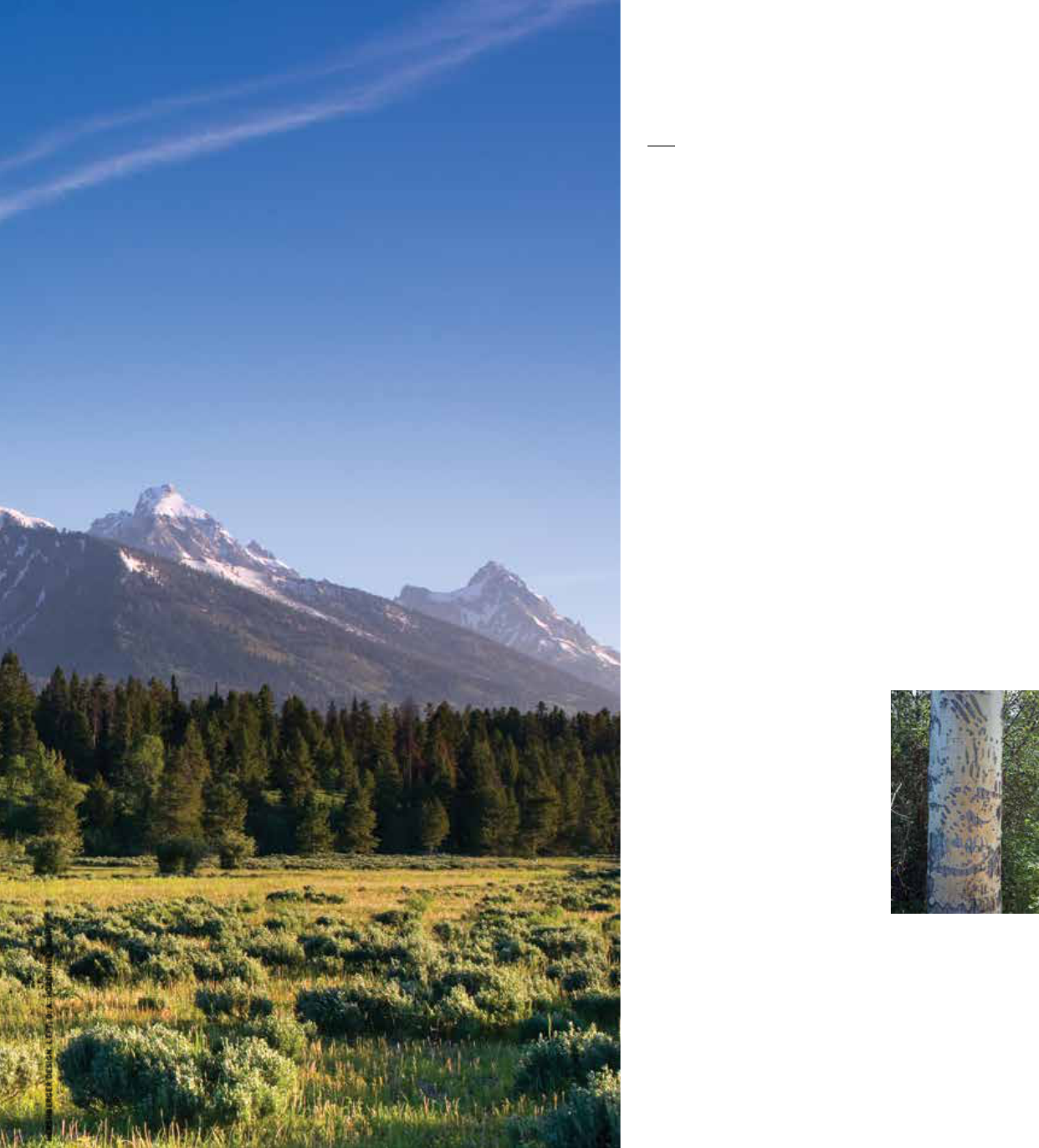

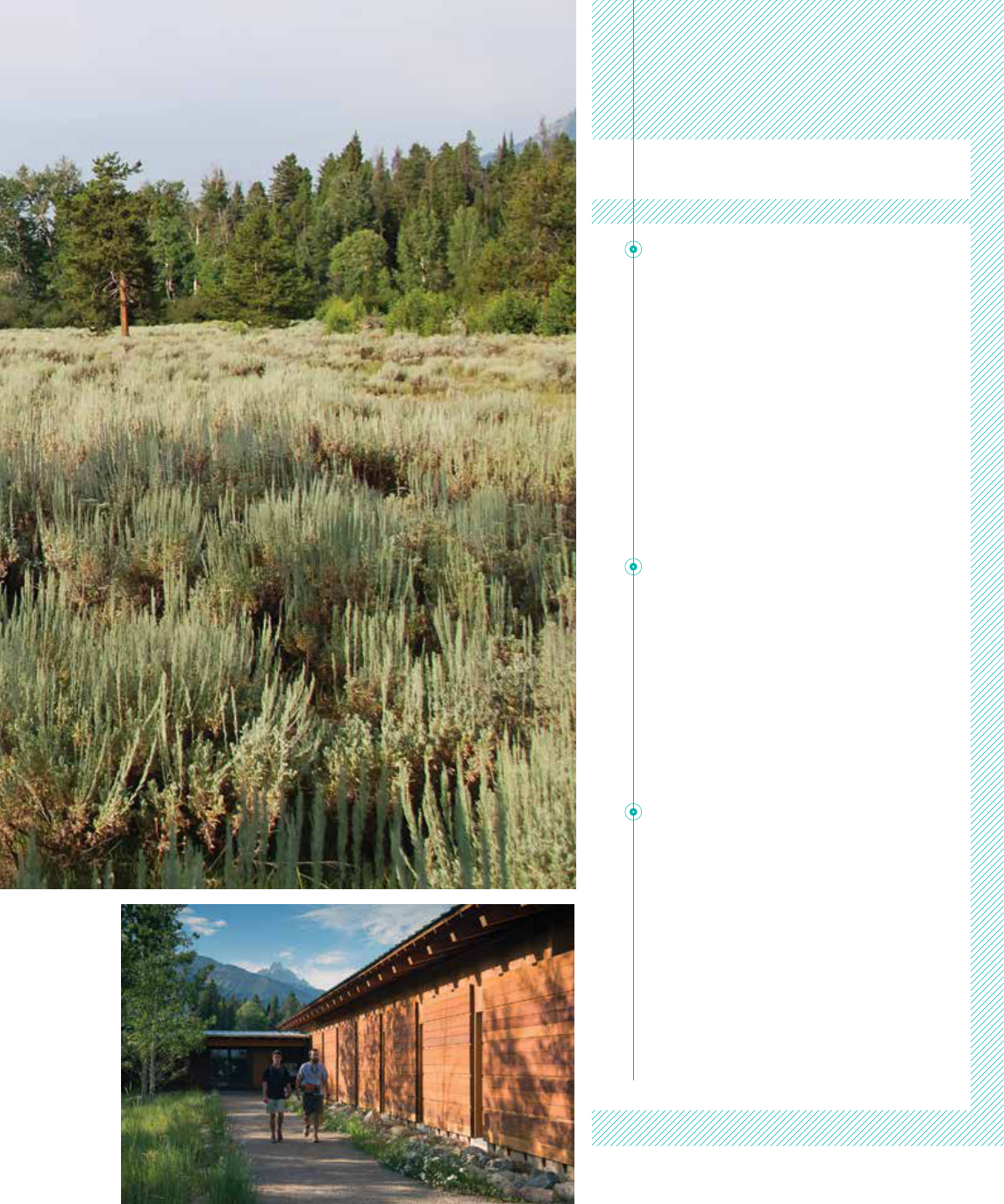

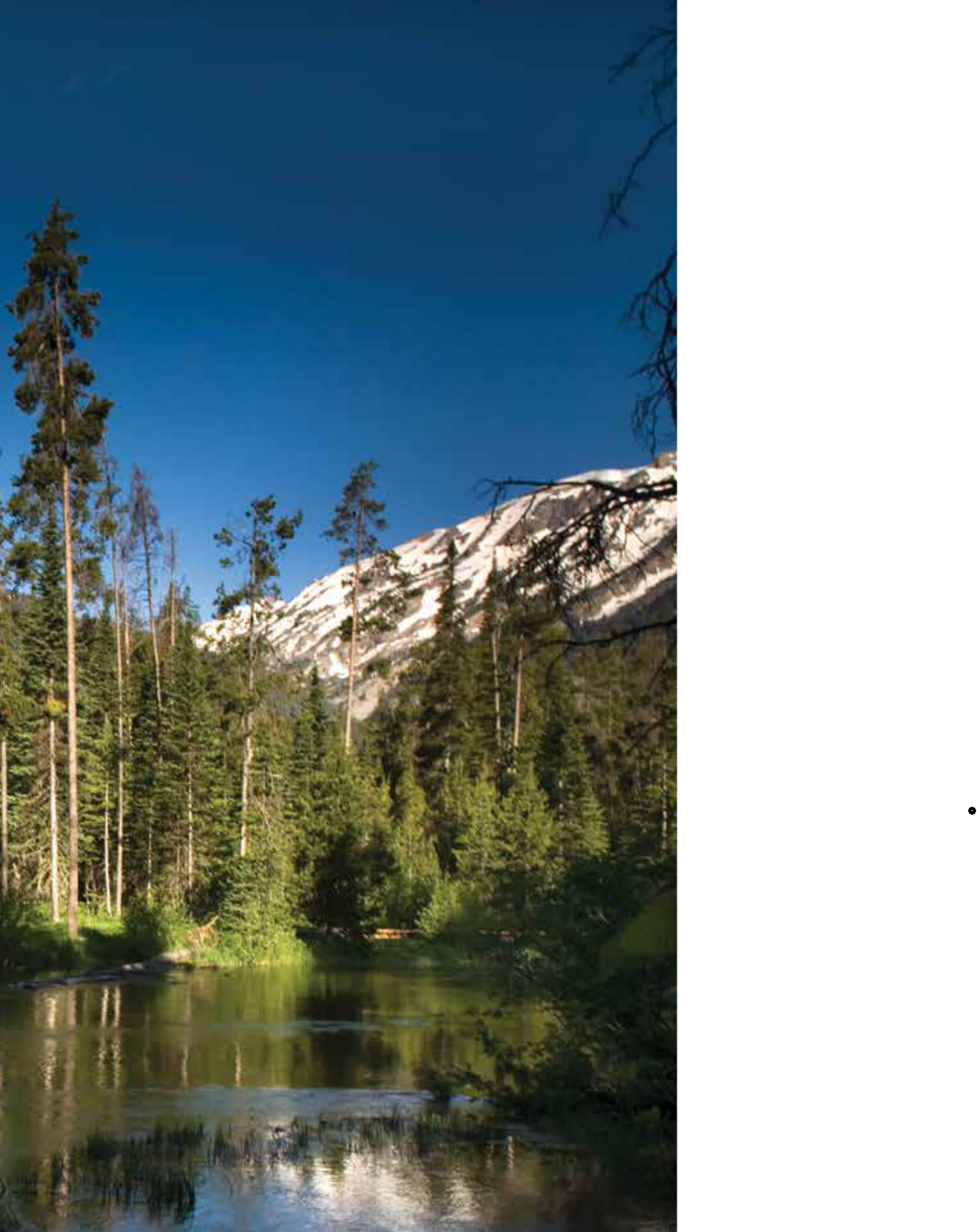

LEFT

The new interpretive

center lies at the

junction of a sagebrush

meadow and the

forest’s edge.

BELOW

Grizzlies and black

bears leave their marks

on an aspen near

the trailhead.

HERSHBERGER DESIGN, LEFT; D. A. HORCHNER, RIGHT

126 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

NIC LEHOUX, TOP; DAVID J. SWIFT, BOTTOM

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

Located 14 miles north of Jackson, Wyoming, near

the southern extremity of Grand Teton National

Park, the preserve was the parting gift of Laurance

S. Rockefeller (1910–2004) and his family to the

National Park Service. Rockefeller worked with

D. R. Horne & Company to develop the preserve

in Wyoming, and the donation was announced in

2001. The land was formally conveyed in 2007.

Rockefeller’s death fell at the midpoint of the

transformational process he had envisioned, but

the Rockefeller Foundation and other groups in-

volved made the decision to stay the course. The

preserve opened to the public in the summer of

2008, and in 2014 it won an ASLA Professional

Honor Award for its many environmentally sensi-

tive features and its distinctive approach to public

engagement with the wilderness.

“He was very, very hands on,” said Mark Hersh-

berger, ASLA, of Laurance Rockefeller. “He wanted

it to be consistent with the family and their whole

ethic of conservation.” Hershberger founded Hersh-

berger Design in 2001 and was later joined by his

wife, Bonny Hershberger, ASLA. The couple met

while working at Design Workshop’s Aspen oce.

“We wanted a practice that focused 100 percent on

the Jackson Hole area. And that’s what we do,” Mark

Hershberger said.

Rockefeller’s lifelong commitment to conservation

and to the national parks in particular is too com-

plex to even summarize here (the Yale historian

Robin Winks published a book on the subject in

1997). This exceptional career was rooted in this

place: The LSR Preserve has taken the place of

the JY Ranch, a dude ranch of some 3,400 acres

purchased by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1932. Laur-

ance Rockefeller’s father conducted an arduous and

often controversial campaign to preserve the Grand

Tetons from encroaching commercial development

by purchasing vast tracts of it through his shell cor-

poration, the Snake River Land Company.

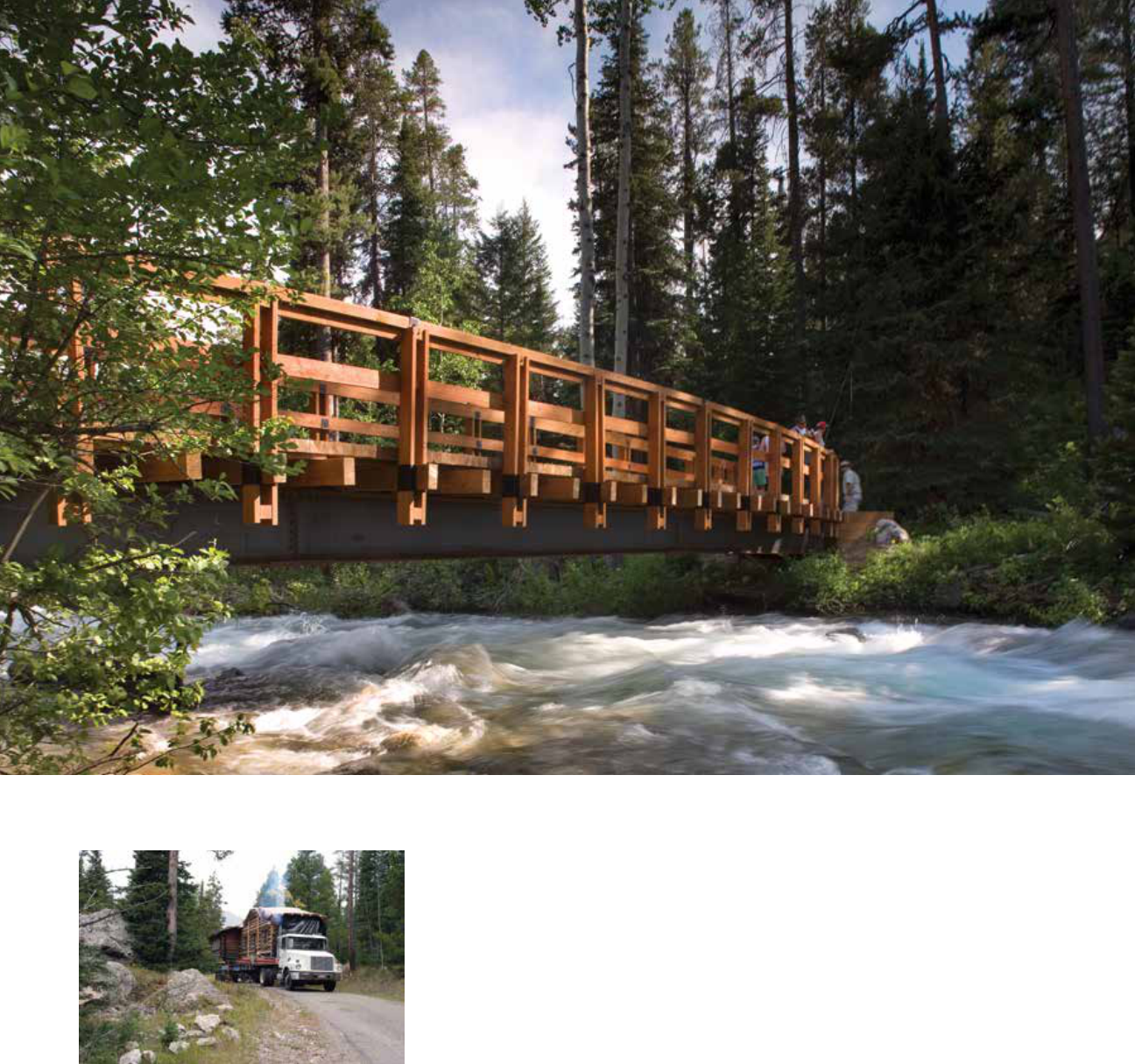

OPPOSITE TOP

The Lake Creek bridge

is built with Douglas fir,

and has a clear span of

recessed steel beams

beneath it.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM

Existing cabins on

the property were

moved by truck

to new locations.

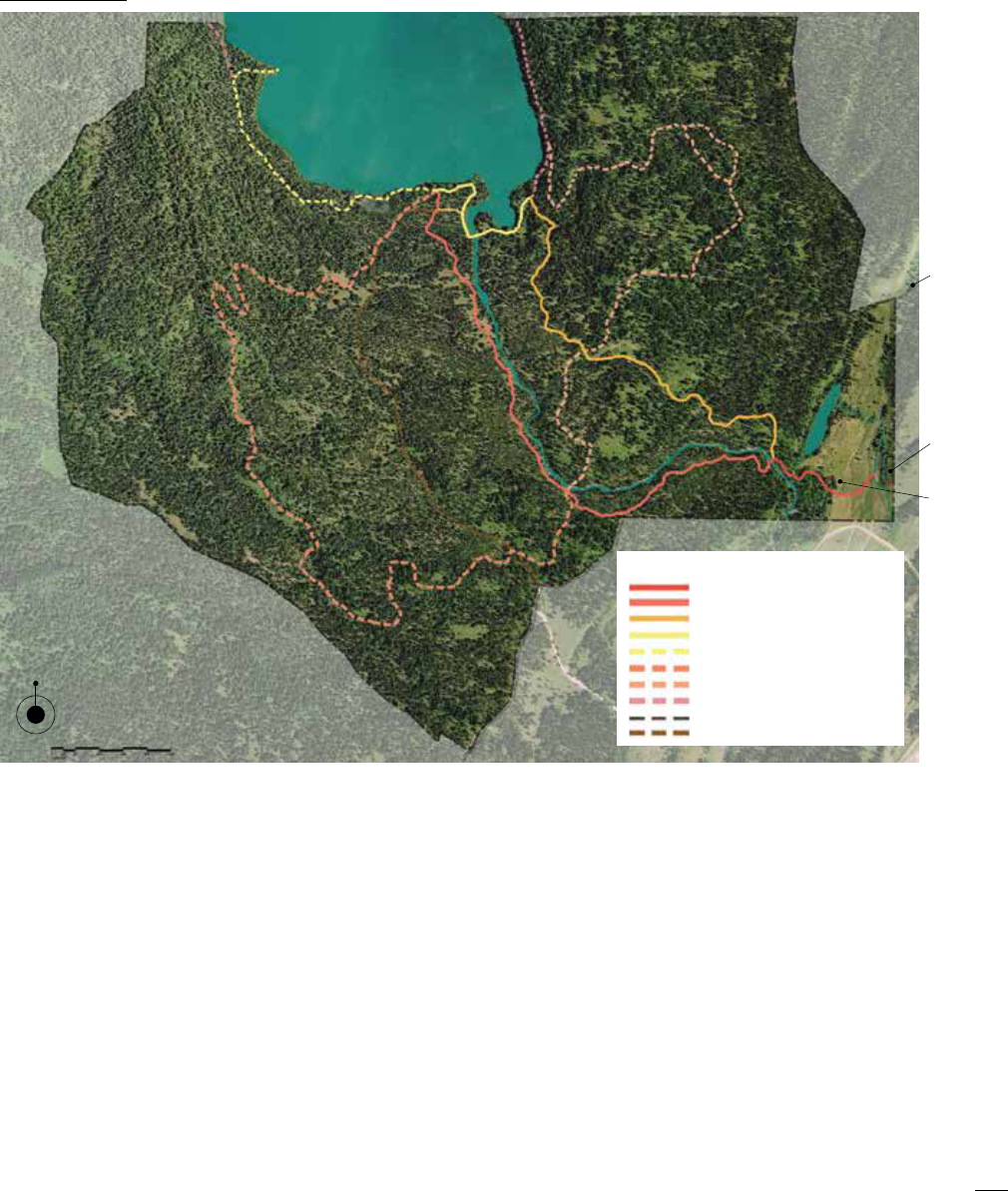

PHELPS LAKE

HUCKLEBERRY

UNDERSTORY

SPRUCE–FIR

FOREST

WETLAND &

SEASONAL

POND

MOUNTAIN & LAKEFRONT

ECOLOGY

OSPREY

HABITAT

GLACIAL

ERRATICS

ENTRY

ROAD

PARKING

LOT

INTERPRETIVE

CENTER

VIEWS–MOUNTAIN

CONTEXT

GLACIAL

TERMINAL

MORAINE

SAGEBRUSH–

STEPPE

COMMUNITY

LAKE CREEK

RIPARIAN

COMMUNITY

LAKESIDE

RIPARIAN

COMMUNITY

LODGEPOLE

PINE FORE ST

STREAM

CASCADE

WOODLAND

MEADOW

ASPEN

COMMUNITY

VIEWS–VALLEY

CONTEXT

ELK MIGRATION

CORRIDOR

N

LEGEND

LAKE CREEK TRAIL ADA .28 MI.

LAKE CREEK TRAIL 1.25 MI.

WOODLAND TRAIL .97 MI.

PHELPS LAKE TRAIL .37 MI.

HUCKLEBERRY POINT TRAIL .69 MI.

ASPEN RIDGE TRAIL 2.36 MI.

BOULDER RIDGE TRAIL 1.71 MI.

PHELPS LAKE LOOP TRAIL .52 MI.

HORSE TRAIL 3.76 MI.

ATV SERVICE ACCESS TRAIL 1.05 MI.

SITE PLAN

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 127

NIC LEHOUX, TOP; DAVID J. SWIFT, BOTTOM

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

Originally a working ranch, JY Dude

Ranch was typical of tourist develop-

ment in Jackson Hole during the

early 20th century. Despite gently

rolling topography with magnicent

views of Albright Peak and ample

water from Phelps Lake and its out-

ow Lake Creek, the thin soil stud-

ded with granite cobble could not

support protable farming. Phila-

delphia entrepreneurs developed

the failed ranch into a fantasy cow-

boy retreat between 1906 and 1929. It housed

up to 65 guests in 48 buildings, including log

cabins, mess halls, stables, and corrals. The

Rockefeller family gently revised the ranch over

the decades but never violated the simplicity of

the place, which indeed verged on the spartan.

“Some of the guest cabins didn’t even have bath-

rooms,” Finlay said.

“For this project, it was more about how do we

erase, how do we take away,” said Bonny Hersh-

berger. “It wasn’t about putting stu there. It was

about how do you take it all away and make it look

like it wasn’t there.” In the six years between the

announcement of the gift and the project’s comple-

tion, every structure on the site, and the bulk of the

roads and trails that had served the JY Ranch, were

removed. The cabins and barns were trucked to

new locations. The architects Carney Logan Burke

of Jackson designed an interpretive center and sev-

eral service buildings to house composting toilets

at key locations within the preserve, among the

rst projects within the park service to be awarded

LEED Platinum status, Finlay told me.

128 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

1

2

3

The preserve is reached by the Moose-Wilson

Road, which intersects the main access route of

the Grand Teton National Park near the main

visitor center. The imprint of Rockefeller’s vision

is evident from the start: The parking lot has space

for only 50 vehicles. Once the lot is full, parking

“ambassadors” keep visitors waiting their turn and

forestall the improvised parking sprawl that mars

String Lake and other popular areas in the park.

The preserve’s new buildings were already in hi-

bernation by the time of my visit, their windows

boarded up against the coming winter. Their

exteriors combine lodgepole pine members with

granite boulders and cobble in a way that evokes

both the dude ranch vernacular as well as the

midcentury modern avor of Jackson Lake Lodge

to the north, built in 1955. The interpretive cen-

ter’s eldstone chimney merges at its base into

free-form groups of granite boulders that edge

its site. Throughout the preserve, stone that was

uncovered during the removal of the buildings

was reincorporated into the design. “Ninety-ve

percent of the boulders that you see out there

were placed,” Mark Hershberger said. Their ap-

pearance is awless: Dings and scrapes from ex-

cavation equipment were later sandblasted away.

A trail that leads from the parking lot takes you

across a fragrant sagebrush meadow to the in-

terpretive center, which stands just at the point

where the meadow gives way to a forest of cot-

tonwoods, aspens, and pines on higher ground.

The trail splits, allowing repeat visitors to bypass

the chapel-like reading room of the center and

head directly into the woods.

4

5

6

7

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 129

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

N

The preserve oers a graded series of experiences

that introduce people to the wilderness. Just past

the interpretive center, a drinking fountain made

of repurposed iron set into a boulder encourages

the lling of canteens, or at least a ritual drink,

before setting o into the woods. The path follows

the edges of a wetland area where a deck and a

broad bench made of a single piece of Douglas

r invite you to pause. The r benches, cut and

milled just over the border in Idaho, are consistent

throughout the preserve. The scale and simple

form—they are just giant slabs—immediately

bring to mind the pioneer minimalist Carl Andre’s

work, as do the boulders that are often placed

near them.

The “front country” section of the preserve is fully

accessible to people with disabilities. The trail is

wide enough for several people to walk abreast.

The elements of the design are meant to engage

you through all your senses. For example, a former

irrigation canal has been recongured to create a

waterfall that can be approached by an expanded-

metal walkway, which lets you place your hands

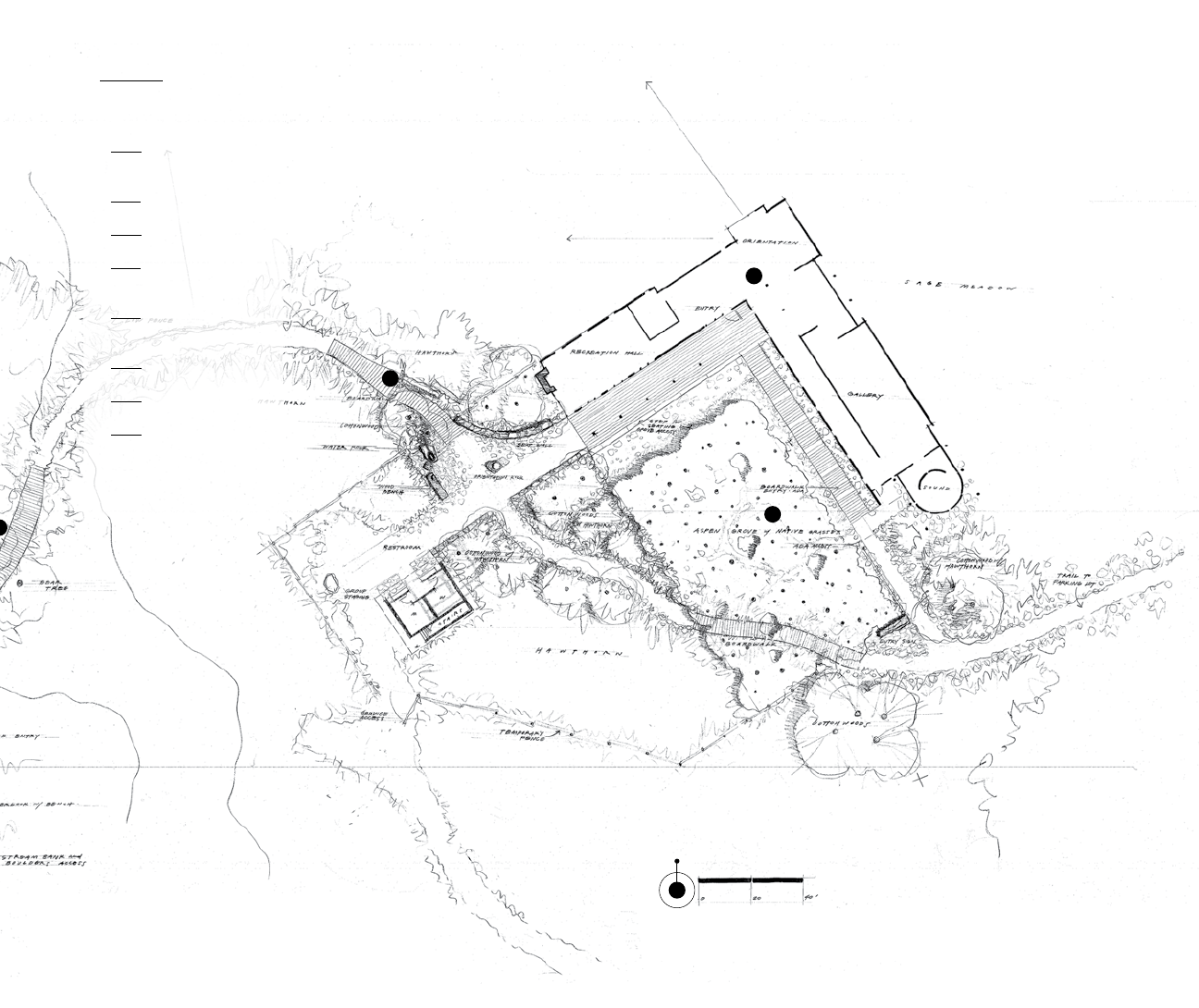

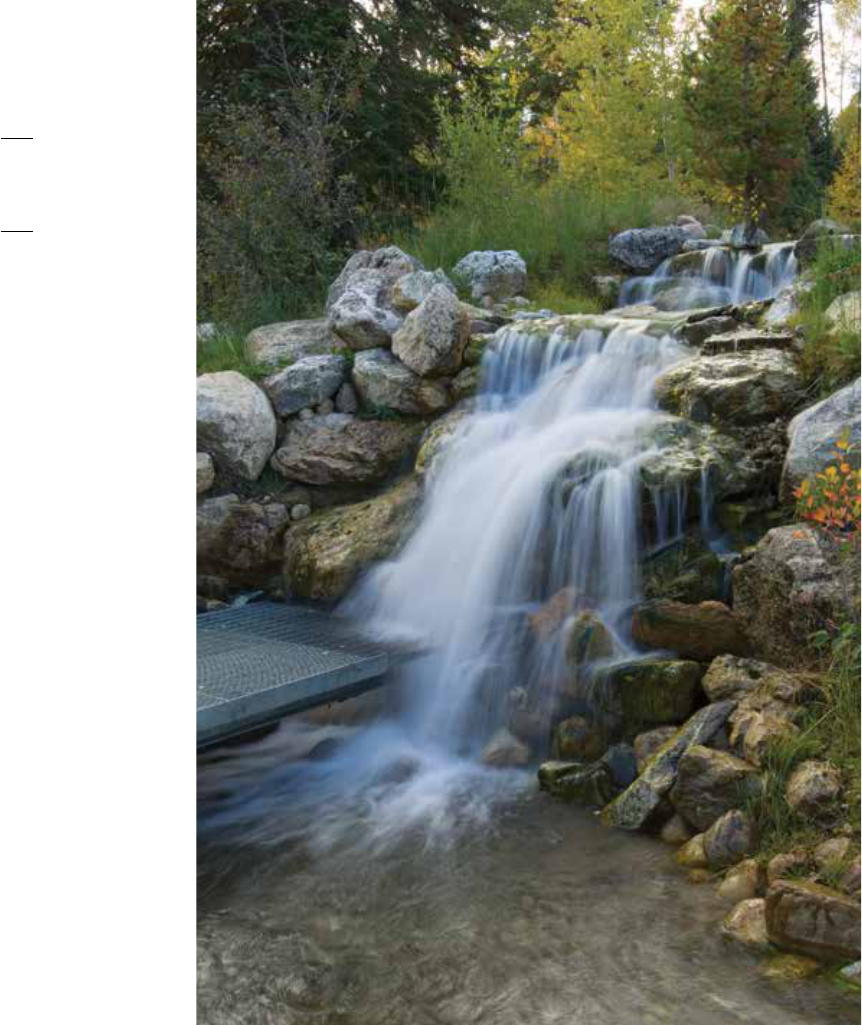

BELOW

The “front country” trails

that lead to the Lake

Creek bridge (at le)

meet ADA standards.

The interpretive center

(below) houses a library

and reading room.

1 PRIMARY TRAIL

TO PHELPS LAKE

2 WOOD BRIDGE

WITH OVERLOOK

3 PRIMARY RETURN TRAIL

4 WOOD BRIDGE

5 WATERFALLS WITH

METAL GRATE BRIDGE

6 DECK OVERLOOK

WITH BENCH

7 BOARDWALK

8 INTERPRETIVE CENTER

9 ASPEN GROVE WITH

NATIVE GRASSES

PLAN

7

7

8

9

130 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

HERSHBERGER DESIGN, TOP; D. A. HORCHNER, BOTTOM

and even your feet in the water. “We wanted folks

who can’t get down and experience water to expe-

rience water,” Mark Hershberger said. “There is

nothing colder than Rocky Mountain stream water.

That water was snow three days ago.”

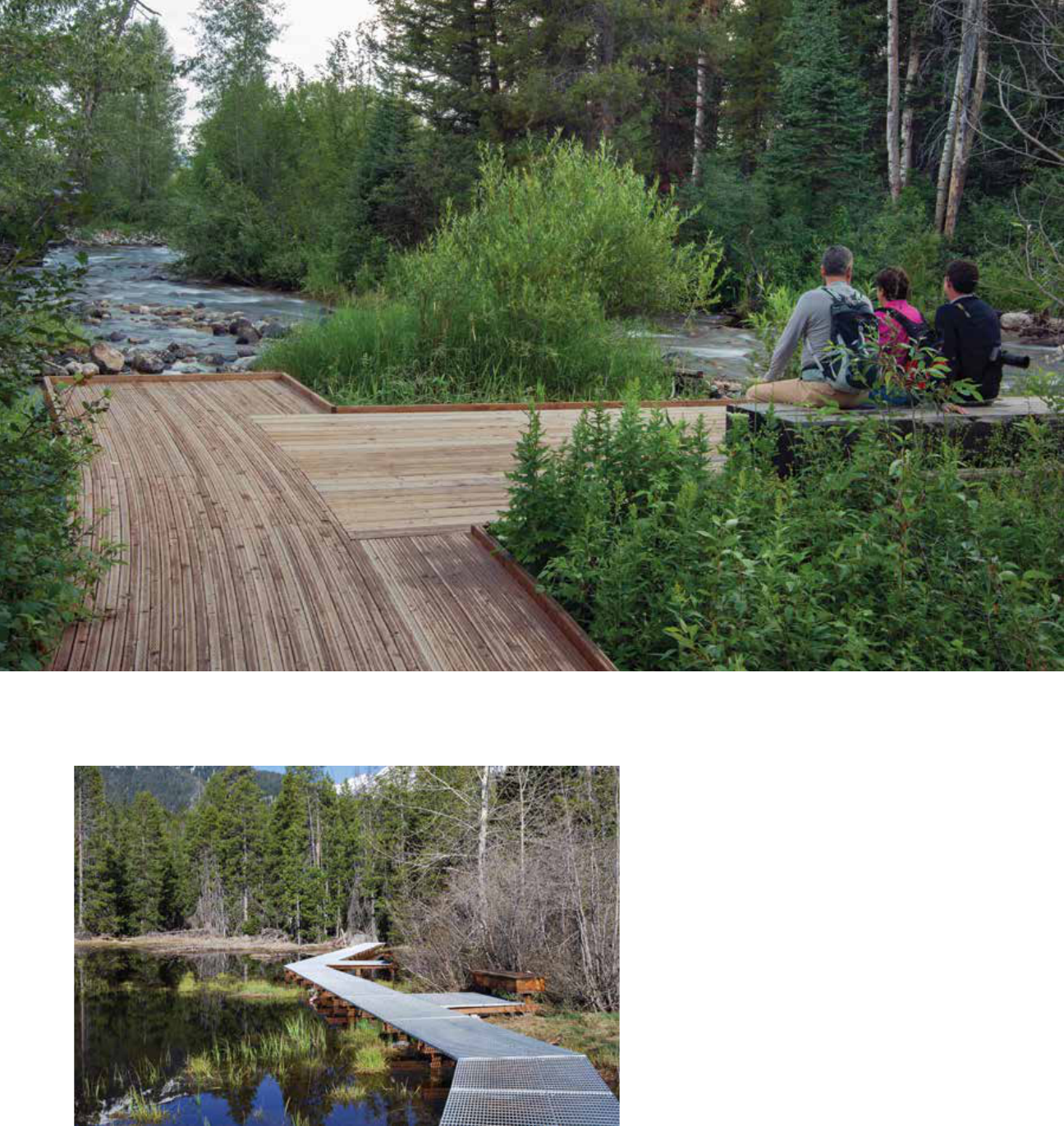

A wooden bridge spans Lake Creek, the point at

which the accessible component of the trail reach-

es its end. As a visual cue, the bridge draws you

out over Lake Creek, and its deck swells outward

to accommodate anyone who pauses to listen to

the stream ow over its rocky bed and watch the

water sparkle. As you step o the far edge of the

bridge, the footing is immediately rougher, a tac-

tile cue that more demanding terrain lies ahead.

The bridge also entices you onto a one-way loop.

The Lake Creek Trail picks up at the far end of

the bridge and carries you to the lakefront. Along

the lakefront, the trail intersects the Phelps Lake

Trail. Another trail, the Woodland Trail, gives

you a natural option to return to the trailhead by

a dierent route, satisfying a sense of exploration.

Keeping you from having to walk against the ow

of trac is just one of the techniques that Hersh-

berger Design used to enhance the meditative

ABOVE

A sage meadow

is now where

a road once was.

OPPOSITE

The interpretive center

is among the national

parks’ first LEED

Platinum buildings.

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 131

HERSHBERGER DESIGN, TOP; D. A. HORCHNER, BOTTOM

PLANT LIST

SEED MIX FOR DRY MEADOW AREAS

Achillea millefolium (Common yarrow)

Achnatherum hymenoides (Indian ricegrass)

Amelanchier alnifolia (Saskatoon serviceberry)

Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata

(Basin big sagebrush)

Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana

(Mountain big sagebrush)

Eriogonum heracleoides (Parsnipflower buckwheat)

Festuca idahoensis (Idaho fescue)

Leymus cinereus (Basin wildrye)

Machaeranthera tanacetifolia (Tansyleaf tansyaster)

Phleum alpinum (Alpine timothy)

Poa alpina (Alpine bluegrass)

Poa secunda (Sandberg bluegrass)

Purshia tridentata (Antelope bitterbrush)

Thinopyrum ponticum (Tall wheatgrass)

PLANTS AND SEED MIX FOR FORESTED AREAS

Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia (Thinleaf alder)

Aquilegia coerulea (Colorado blue columbine)

Ceanothus velutinus var. velutinus

(Snowbrush ceanothus)

Crataegus douglasii (Black hawthorn)

Geranium viscosissimum (Sticky purple geranium)

Mahonia repens (Creeping barberry)

Pinus contorta (Lodgepole pine)

Populus tremuloides (Quaking aspen)

Prunus virginiana (Chokecherry)

Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir)

Symphoricarpos albus (Common snowberry)

PLANTS AND SEED MIX FOR WETLANDS AREAS

Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia (Thinleaf alder)

Calamagrostis canadensis (Bluejoint)

Carex aquatilis (Water sedge)

Carex nebrascensis (Nebraska sedge)

Cornus sericea (Red osier dogwood)

Crataegus douglasii (Black hawthorn)

Deschampsia cespitosa (Tued hairgrass)

Eleocharis palustris (Common spikerush)

Juncus torreyi (Torrey’s rush)

Populus angustifolia (Narrowleaf cottonwood)

Salix exigua (Narrowleaf willow)

Schoenoplectus acutus var. acutus

(Hardstem bulrush)

Scirpus microcarpus (Panicled bulrush)

Typha latifolia (Broadleaf cattail)

132 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

HERSHBERGER DESIGN, TOP; D. A. HORCHNER, BOTTOM

mood of the preserve. “I spent a lot of time in the

mountains,” Mark Hershberger said. “I spent a

lot of time hiking.” The sense of solitude of the

deep woods can be found remarkably close to

the entrance of the preserve. The entire loop is

just 2.9 miles long, just an hour or two for an

average hiker.

The shore of Phelps Lake opens to magnicent

views of Albright Peak, some 10,552 feet high,

and Death Canyon. Two huge Douglas rs mark

the site of the main lodge of the JY Ranch, where

a bench and a grouping of boulders now form a

viewing area that faces the mountain range. As I

hiked out to watch the sunrise there, mule deer

and red-tailed hawks were my only companions.

Viewed from the lakeshore, the mountains are

illuminated from their peaks downward, as if they

were shrugging o a dark curtain.

BOTTOM

A small parking area

is monitored to control

the number of visitors

in the preserve.

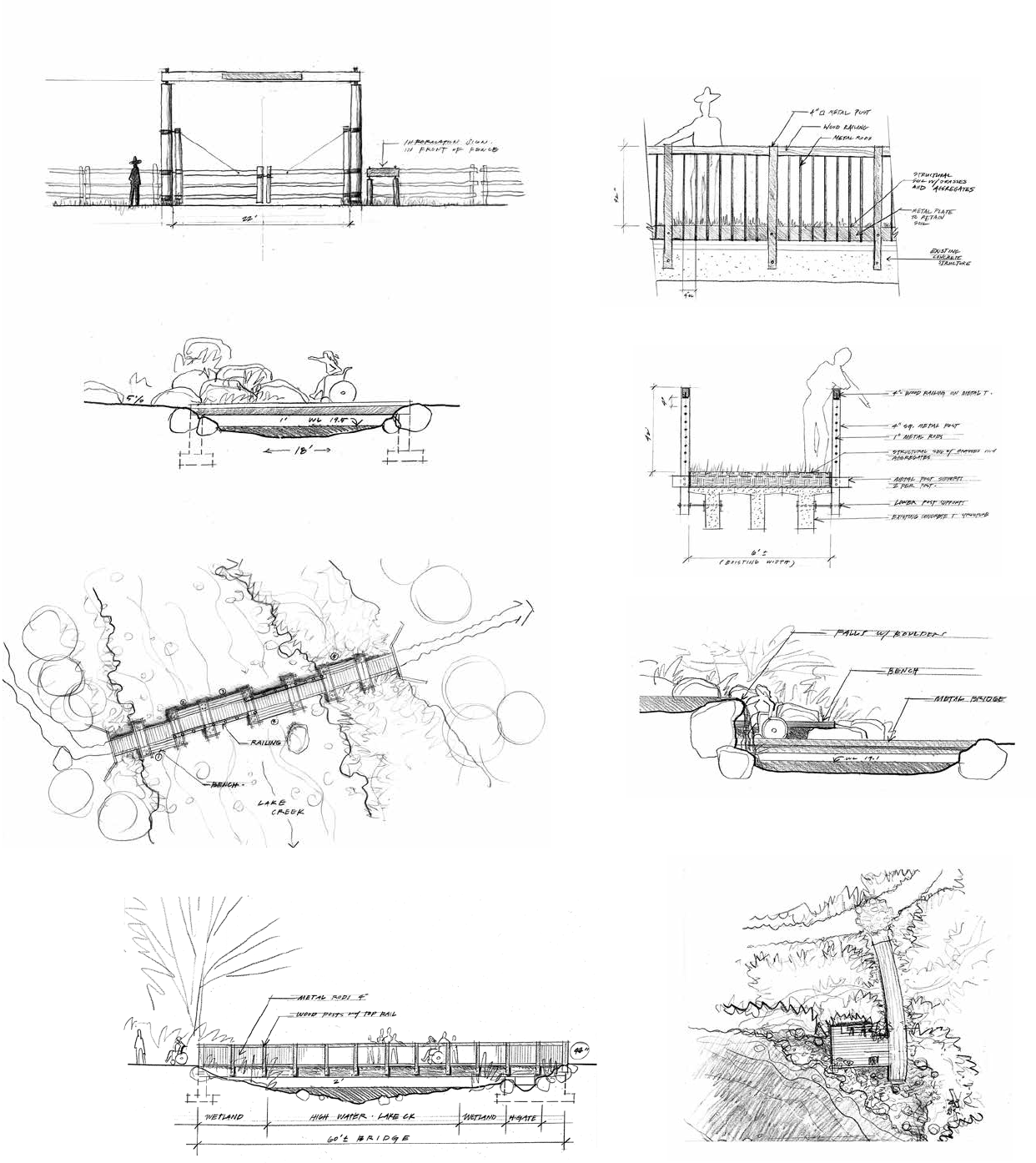

OPPOSITE

Hershberger Design

created a range of

functional elements in

keeping with the site’s

history.

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 133

HERSHBERGER DESIGN

HERSHBERGER DESIGN, TOP; D. A. HORCHNER, BOTTOM

ENTRY GATE

PLATFORM BRIDGE

SITTING BRIDGE

SOD BRIDGE ELEVATION

SOD BRIDGE

LAKE CREEK BRIDGE

LAKE CREEK OVERLOOK

WATERFALLS

134 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

D. A. HORCHNER, TOP; HERSHBERGER DESIGN, BOTTOM

D. A. HORCHNER

Other benches and groupings of stones have been

placed at intervals along the shore to encourage a

deeper connection with aspects of the view and

the setting. Before the gift of the land was made,

the Rockefeller property blocked o the southern

portion of the lake. A loop trail now follows the

contours of Phelps Lake and rejoins the backcoun-

try trails that lead up into the canyon and beyond.

A wooden bridge that once carried automobiles to

the center of the ranch has been recongured as a

place to gather and enjoy the headwaters of Lake

Creek. Metal decking snakes across a wetland area,

allowing an intimate experience of the lacustrine

ecosystem. A whole palette of options opens up

for the visitor.

The Hershberger Design team provided additional

trails within the preserve to oer people the chance

to go more deeply into its terrain. The Boulder

Ridge Trail loops due east, into somewhat more

elevated ground. To the west, the Aspen Ridge Trail

takes a longer route to return to the interpretive cen-

ter. Hiking out this trail at sunset, I found myself on

the heels of a herd of elk who left their distinctive,

slightly sharp scent on the air behind them.

Jackie Skaggs, a former spokesperson for Grand

Teton National Park, has reported that something

on the order of $20 million was spent to develop

the preserve, much of it spent removing the traces

RIGHT

A waterfall cascades

over the bed of a

former irrigation canal.

Metal grating allows

the water to flow

through the path itself.

OPPOSITE TOP

This curved wooden

boardwalk overlooks a

stretch of Lake Creek.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM

A metal boardwalk

traverses a wetlands

area.

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 135

D. A. HORCHNER, TOP; HERSHBERGER DESIGN, BOTTOM

D. A. HORCHNER

of decades of occupation of the site. (Many of the

buildings were transferred to a new Rockefeller

property outside the park, and others were given

to the National Park Service for reuse.) Rockefeller

was well aware that his own vision for the land

could not be carried out by the park service itself.

First and foremost, historic preservation protocols

would have kept the JY Ranch intact. Further-

more, funding for a restoration project of this scale

would have been next to impossible to obtain.

As the longtime Grand Teton guide and philoso-

pher Jack Turner has said, “If you’ve never had a

genuine wilderness experience…then why would

you be drawn to it? That’s why it’s so important

for those of us who love wild places and wild

animals—and what happens to our minds when

we’re in their presence—to do our best to get

people out there and help bring them into the

experience.” The national parks face the challenge

136 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016

NIC LEHOUX

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE AUG 2016 / 137

of balancing wild nature, with its inherent risks

and uncontrollability, with the diverse needs of an

Internet-connected and heavily stimulated public.

Laurance S. Rockefeller’s intent was to provide a

new paradigm for the parks of the 21st century,

one that balances education, entertainment, and

the silent meeting of the wild. With the help of

Hershberger Design and the national parks com-

munity, he found a formula that works.

PHILIP WALSH IS A WRITER BASED IN CENTRAL MASSACHU-

SETTS. HE CAN BE REACHED AT

PHILIPW[email protected].

Project Credits

CLIENT NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, JACKSON, WYOMING. OWN-

ER REPRESENTATIVE D. R. HORNE & COMPANY, ARLINGTON,

VIRGINIA. PROJECT MANAGEMENT CLAY JAMES, JACKSON,

WYOMING. ARCHITECT CARNEY LOGAN BURKE ARCHITECTS,

JACKSON, WYOMING. LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT HERSHBERGER

DESIGN, JACKSON, WYOMING. SITE ASSESSMENT/RECLAMA-

TION PIONEER ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES, LOGAN, UTAH.

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER KL&A, INC., DENVER. CIVIL ENGINEER/

SURVEYOR JORGENSEN ASSOCIATES, JACKSON, WYOMING. LEED

CONSULTANT ROCKY MOUNTAIN INSTITUTE, BASALT, COLORADO.

INTERPRETIVE SIGNAGE AND EXHIBIT DESIGNER THE SIBBETT

GROUP, SAN ANSELMO, CALIFORNIA. MECHANICAL SYSTEMS

ME ENGINEERS, DENVER. LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID NELSON

& ASSOCIATES, LITTLETON, COLORADO. LEED COMMISSIONING

ENGINEERING ECONOMICS INC., GOLDEN, COLORADO. GENERAL

CONTRACTOR GE JOHNSON CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, JACKSON,

WYOMING. TIMBER FRAME/WOOD PRODUCTION SPEARHEAD

INC., NELSON, BRITISH COLUMBIA.

LEFT

This repurposed

vehicular bridge oers

tiered seating at the

Lake Creek headwaters

on Phelps Lake.

NIC LEHOUX