Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yhrj20

Hispanic Research Journal

Iberian and Latin American Studies

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yhrj20

Enlightenment Erasure: The Lost Seventeenth

Century in Spanish Architectural History

Jesús Escobar

To cite this article: Jesús Escobar (2022) Enlightenment Erasure: The Lost Seventeenth

Century in Spanish Architectural History, Hispanic Research Journal, 23:5, 430-451, DOI:

10.1080/14682737.2023.2249385

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14682737.2023.2249385

Published online: 02 Nov 2023.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Enlightenment Erasure: The Lost Seventeenth Century

in Spanish Architectural History

Jes

us Escobar

Department of Art History, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

ABSTRACT

This article addresses the curious absence of seventeenth-century

buildings in traditional histories of Spanish architecture. Beginning

with the Noticias de los arquitectos y la arquitectura en Espa

~

na,a

foundational work published in 1829, the article traces the legacy

of a Spanish Enlightenment myth about the seventeenth century

as a time of a weak monarchy whose overly ornamental

architecture can be understood as a reflection of political

decadence. The article surveys nineteenth and twentieth-century

responses to the Noticias by Spanish, German, and English-

language scholars, proposing that the existing scholarship’s

overriding concern with style be replaced with a renewed focus

on the institutions and individuals who shaped architectural

undertakings in the transatlantic realm of the Spanish Habsburgs.

RESUMEN

Este estudio se enfoque en la curiosa ausencia de edificios del

siglo XVII en las historias tradicionales de la arquitectura espa

~

nola.

Empezando con las Noticias de los arquitectos y la arquitectura en

Espa

~

na, obra fundadora publicado en 1829, el art

ıculo rastrea el

legado de un mito de la Ilustraci

on que trata del siglo XVII como

una

epoca definida por una monarqu

ıad

ebil cuya arquitectura

ornamental se puede intepretar como reflecci

on de la decadencia

pol

ıtica. El art

ıculo repasa las respuestas de estudiosos espa

~

noles,

alemanes, y anglohablantes a las Noticias y propone que la

principal preocupaci

on existente sobre el estilo se reemplace por

un enfoque renovado en las instituciones e individuos que

emprendieron proyectos arquitect

onicos en el dominio

transatl

antico de los Habsburgo espa

~

noles.

KEYWORDS

Architecture; baroque;

Enlightenment; Habsburg;

historiography;

neoclassicism; Spain; style

PALABRAS CLAVE

arquitectura; barroco;

Espa

~

na; estilo; la Ilustraci

on;

Habsburgo; historiograf

ıa;

neoclasicismo

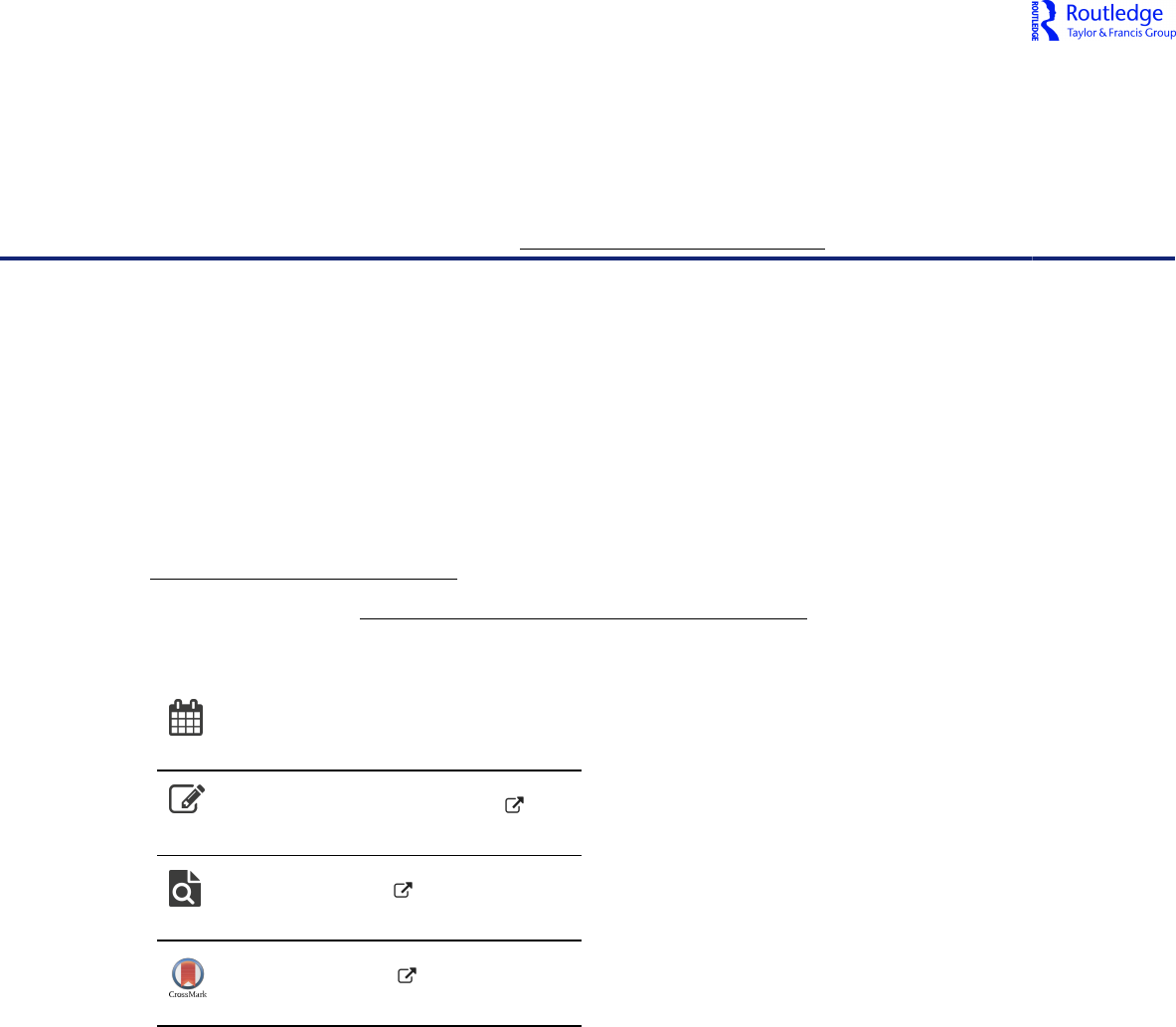

In the early 1770s, Spain’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts hired masons to transform the

fac¸ade of its new home, the Goyeneche Palace (Figure 1). Erected nearly fifty years

earlier, the building located along Madrid’s fashionable Calle de Alcal

a had been

purchased to serve as the seat of what was still a relatively new institution. The

Academy had been granted a royal charter in 1744 and was formalized by royal edict

ß 2023 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

CONTACT Jes

1880 Campus Drive Kresge 4305, Evanston, IL 60208 USA.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL

2022, VOL. 23, NO. 5, 430–451

https://doi.org/10.1080/14682737.2023.2249385

eight years later.

1

From its early days, academicians carried out their work in cramped

quarters located in Madrid’s Plaza Mayor. The sizeable Goyeneche Palace was intended

to facilitate the organization’s ever-expanding societal mission by providing professors

and students with studios, lecture halls, and galleries for painting, sculpture, and

Figure 1. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, formerly Palacio de Goyeneche, Madrid,

1722–32, view of fac¸ade as modified c.1773–74 and subsequently renovated in 1973–83. Photo:

Paul Hermans, Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 3.0.

1

For the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando’s history, see Juan Agust

ınCe

an Berm

udez, Diccionario

hist

orico de los m

as ilustres profesores de las Bellas Artes en Espa

~

na (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1800), vol. 3, 251;

Carlos Sambricio, La arquitectura espa

~

nola de la Ilustraci

on (Madrid: Consejo Superior de los Colegios de

Arquitectos de Espa

~

na, 1986).

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 431

architecture, as well as an entire floor dedicated to the display of an important natural

history collection.

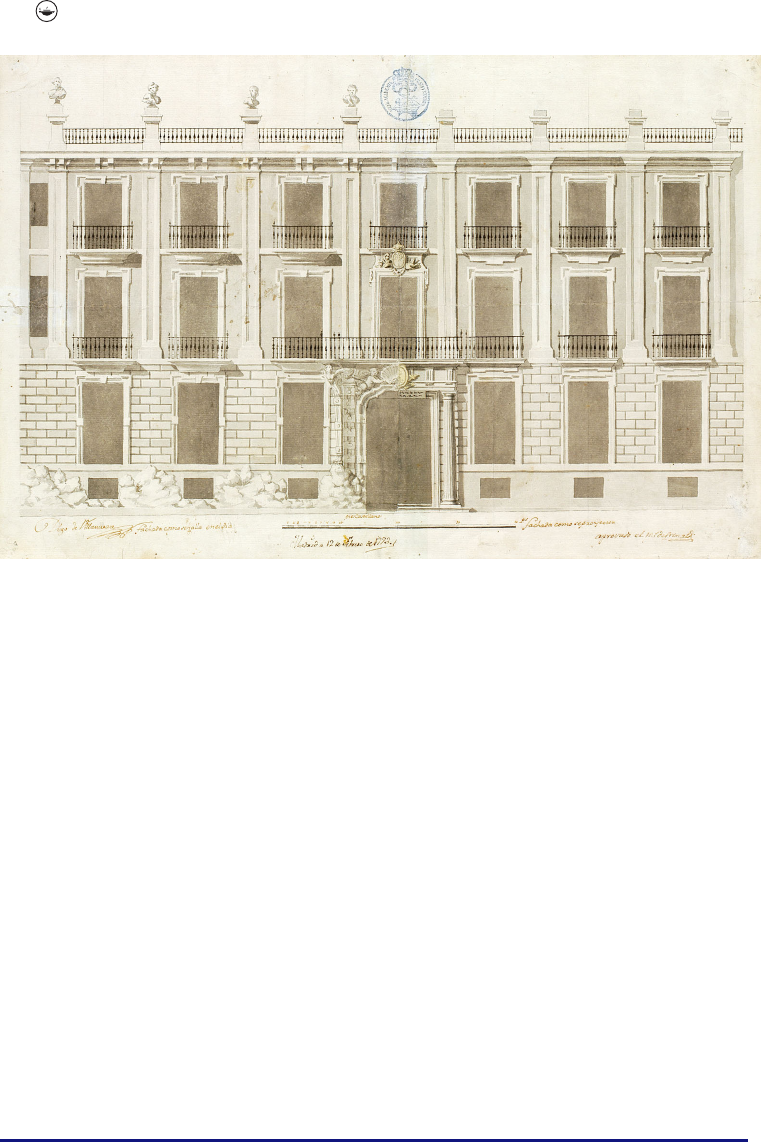

At street level, scars from the effacement of Goyeneche Palace in the 1770s remain

evident to the passerby. They are easier to see by examining a period drawing made by

Diego de Villanueva (1715–74) (Figure 2).

2

Villanueva was one of two Directors of

Architecture at the Royal Academy and older brother of Juan de Villanueva, the

Spanish architect most closely associated with eighteenth-century classicism. In his

drawing, Diego depicts the Goyeneche Palace fac¸ade as seven bays wide and four stories

tall with an ornamental portal marking the building’s center. Keeping with local

practice, the windows of the upper stories are fronted by balconies and the whole

composition is crowned with a balustrade. On the left half of the sheet, Villanueva

records the fac¸ade “as it appears today” (“como se halla en el dia”), a notation that

appears next to his signature at lower left. Noteworthy features include a rusticated

ground story, colossal pilasters, and sculpted busts along the roofline. To the right,

Villanueva portrays the palace fac¸ade “como se proyectta”, or as planned.

Figure 2. Diego de Villanueva, Drawing of the fac¸ades of the Palacio de Goyeneche and Royal

Academy of Fine Arts, Madrid, c. 1773–74, black ink with gray and yellow washes on paper,

14.1 21.2 in. (359 538 mm). Biblioteca de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando,

Madrid, INV-2216. Photo: # Biblioteca de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

2

On the drawing, see Joaqu

ın Ezquerra del Bayo, “La Casa de la Real Academia de San Fernando,” Revista de la

Biblioteca, Archivo y Museo 8, no. 29 (1931), 36–40; Alfonso Rodr

ıguez G. de Ceballos, “Jos

e de Churriguera, Juan

de Goyeneche y la sede de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando,” Academia 112–13 (2011), 57–86;

Beatriz Blasco Esquivias, Nuevo Bazt

an: La utop

ıa colbertista de Juan de Goyeneche (Madrid: C

atedra, 2019), 317–27.

For Villanueva, see Sambricio, La arquitectura.

432 J. ESCOBAR

Villanueva’s rendering of the main portal capsulizes the proposed transformation. To

the left, a thick, banded est

ıpite, or tapered pilaster, appears to rise from a stone

mountain. A griffin crowns the est

ıpite and a winged putto supports a shell at the apex

of a poly-lobed arch over the doorway. For an architect like Villanueva—a man whose

theoretical writings reflected Enlightenment philosophy and an awareness of recent

archaeological discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii in the Spanish Kingdom of

Naples—the portal’s ornament was excessive and embarrassing. His proposed

correction is emphatically architectonic. A load-bearing Doric column marks the

portal’s right edge supporting an architrave and balcony above. With his watercolour

brush, Villanueva makes the column cast a shadow onto the fac¸ade wall. It is one of the

only standout features of an otherwise pedantic image. Villanueva’s erasure of the

palace’s ornament, however, was nothing short of polemical. His proposed reform

aimed to make manifest in stone a late-eighteenth-century aversion to what has come to

be called baroque architecture.

Juan de Goyeneche, the original patron of the palace on the Calle de Alcal

a, was born

in 1656. A successful entrepreneur, he served as a financial minister to the last Spanish

Habsburg king, Carlos II (1661–1700; reg. 1675–1700). With the arrival of Bourbon

monarchs to the Spanish throne in 1700—a position not guaranteed until after a

fourteen-year war with Austrian Habsburg rivals—Goyeneche played a pivotal role in

maintaining the realm’s financial stability. As a publisher and proto industrialist, he also

became a leading figure in the cultural life of Madrid until his death in 1735, as Beatriz

Blasco demonstrates in an important recent study.

3

When, in 1722, he purchased six

properties to build a palace, Goyeneche opted for a design by Jos

e Benito Churriguera

(1666–1725). Churriguera headed a family of prolific builders whose expertise included

multi-tiered, multi-media retablos, a term that can be roughly translated as altarpieces.

In the early modern period, retablos were considered works of architecture although, in

recent times, they have been categorized as sculpture. The designation is technical, yet it

hints at a critique in Villanueva’s academic circles that labeled Churriguera an “artist-

architect” prone to employing excessive ornament. Already in the 1770s, Jos

e Benito’s

family name gave rise to the disparaging label, churrigueresco, a term that is still in use

and even has an English-language variant.

4

Moreover, the period in which Churriguera worked—the late seventeenth and early

eighteenth centuries—came to be called a time of “plague” in the foundational work of

Spanish architectural history, Noticias de los arquitectos y arquitectura de Espa

~

na

(Notices on the architects and architecture of Spain, hereafter Noticias). Written by

Eugenio Llaguno y Amirola (1724–99) and edited by Juan Agust

ınCe

an Berm

udez

(1749–1829), two Enlightenment officials who shared Villanueva’s convictions, the

Noticias was published in four volumes in 1829. It established a model for vilifying the

kind of architectural ornament that gained popularity in the seventeenth century in

Spain. These ornamental tendencies were redeemed slightly in the middle of the

nineteenth century before being cursed anew at the century’s end as Spanish historians

condemned the seventeenth-century reign of Habsburg rulers as a period of political

3

For Goyeneche’s biography, see Blasco Esquivias, Nuevo Bazt

an,27–131.

4

On the churrigueresco label, see Alfonso Rodr

ıguez G. de Ceballos, Los Churriguera (Madrid: Consejo Superior de

Investigaciones Cient

ıficas, 1971), 9–11.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 433

decline. In the twentieth century, under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco from 1939

to 1975, the Fascist appropriation of Spanish Habsburg architectural forms—most

notably, Philip II’s (1527–1598; reg. 1556–98) monastery-palace of San Lorenzo el Real

de El Escorial—complicates the story even further. The result is that seventeenth-

century architecture in Spain is poorly understood on its own merits.

A 1972 Spanish-language translation of Christian Norberg-Schulz’s Architettura

barocca, first published in Milan in 1971 and concerned with the baroque as an

international style, berates Spanish seventeenth-century architecture, asserting that “the

buildings in and of themselves contribute nothing of importance to the history of

architecture.”

5

It is a strong statement, yet one that saw the light of day in Spain because

of the persistence of the Enlightenment critique established in the ambit of the Royal

Academy and codified by Llaguno and Ce

an’s Noticias. The present essay reassesses the

historiography of Spanish seventeenth-century architecture. It begins with a

consideration of Llaguno and Ce

an’s Ur text which, although published in 1829, was

begun in the 1760s during a period of social and cultural reforms. Next, I highlight the

work of Spanish and German scholars who, in their research published between 1848

and 1908, responded to the critique in the Noticias of what came to be called the

baroque over the course of the nineteenth century. As Norberg-Schulz’s words attest,

the application of the term baroque in Spain was almost exclusively limited to

eighteenth-century buildings such as the Goyeneche Palace, resulting in what I call a

lost seventeenth century in Spanish architectural history.

As a means out of this conundrum, a deeper consideration of politics and

institutional governance in the Spanish Habsburg domain offers a useful model for

thinking about seventeenth-century architecture. Taking up the cases of two

architects overlooked in the historiography, I suggest that the institutions and

individuals for whom they worked can help us examine early modern architecture

in a new light, allowing even the possibility of linking building enterprises on both

sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Careful attention to cultural production in seventeenth-

century Spain matters as historians seek to write a global history of architecture in

the twenty-first century, doing away with a nearly two-hundred-year-old model

whose utility has run its course.

An Enlightenment History of Spanish Architecture

The term baroque as a category of style emerged in the nineteenth century. In Spain, its

characteristics are multi-faceted, owing to geographical factors such as regional building

materials and local construction techniques. Churriguera’s classicism, for instance,

echoes the tradition in Castile of symmetrical compositions often framed by twin

towers, faced with brick or stone, and topped by fanciful slate roofs that betray Flemish

5

Norberg-Schulz, Arquitectura barroca, trans. Luis Escolar Bare

~

no (Madrid: Aguilar, 1972), 327. The statement is

embedded in a passage that includes a sweeping dismissal of Indigenous Americans: “En general, la arquitectura

espa

~

nola del siglo XVII fue tendiendo hacia el decorativismo, que representa una variante del tema barroco de la

persuasi

on. Es natural que alcanzara su cima en los edificios misionales de Am

erica. Aun los analfabetos de una

civilizaci

on ajena pueden ‘entender’ el lenguaje de la ornamentaci

on exuberante, los colores y las im

agenes. Se

halla, por tanto, una actitud t

ıpicamente ‘barroca, ’ pero los edificios por s

ı mismos no representan ninguna

contribuci

on importante a la historia de la arquitectura.”

434 J. ESCOBAR

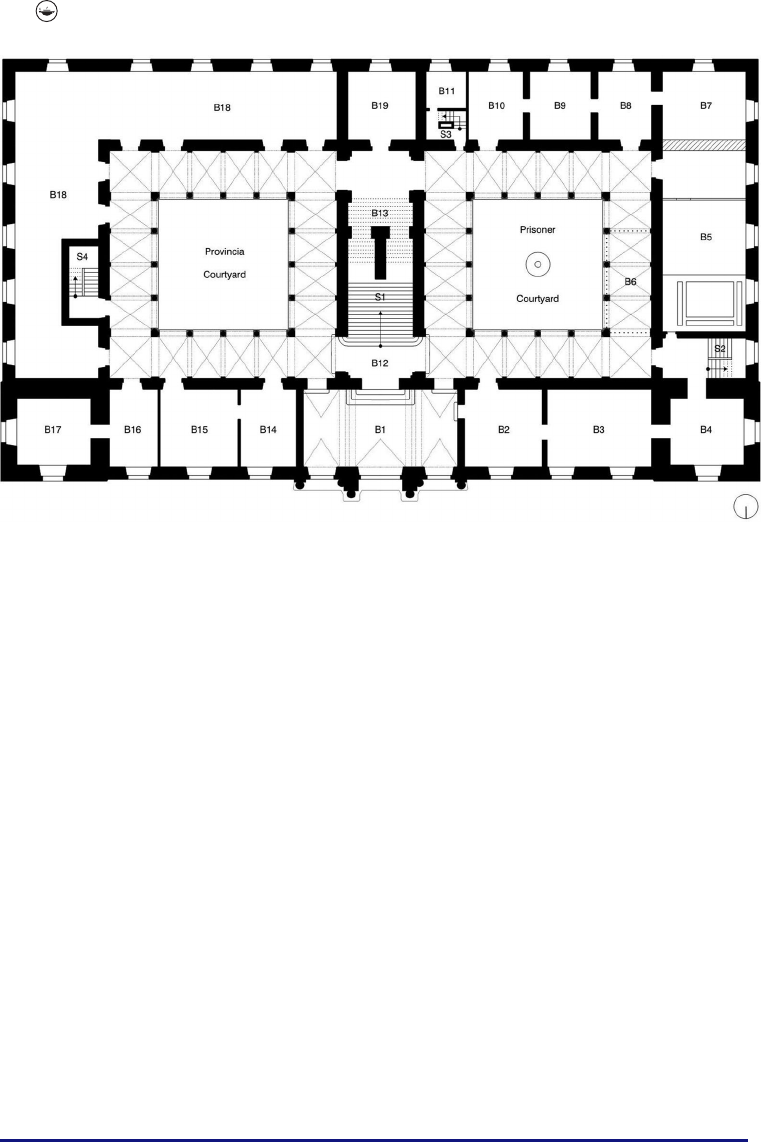

influences. Similar concerns with symmetry can be found in a monument such as the

Obradoiro fac¸ade of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, one of the most famous

of Spanish baroque monuments (Figure 3). Realized over seven decades beginning in

the 1660s and completed with a 1738–49 project designed by Fernando de Casas Novoa

(1670–1749), the fac¸ade fronts a Romanesque building whose height is accentuated by a

late seventeenth-century tower at the top of a large staircase. That tower was matched

by another and the space between filled in with a spectacular stone frontispiece with

Figure 3. Obradoiro fac¸ade, Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Torre del Reloj (at right) by Jos

e

Pe

~

na de Toro and Domingo de Andrade, 1665–71; frontispiece and matching tower by Fernando

de Casas Novoa, 1738–49. Photo by author.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 435

great quantities of glass.

6

The resulting design displays a mastery of geometry in its

design and yet discussions of this fac¸ade tend to ignore the underlying mathematical

order, focusing instead on ornamental features which have been characterized as “small

and charming things.”

7

With the restoration of the fac¸ade, completed in 2019, a viewer

today can appreciate an aesthetic of fine cut stone adorned at key junctures with bronze

ornament and thereby eschew romantic interpretations inspired in part by the lichen

and moss that once covered, and will again cover, the building. The Obradoiro fac¸ade of

carved stone contrasts with the layered textures of tiles and brick that often front

buildings labeled baroque in Seville, Granada, and throughout the southern region of

Andaluc

ıa. Rich tilework and relief ornament also feature in some seventeenth-century

Mediterranean regions, in places such as Valencia and Barcelona.

There is no single Spanish baroque style, an actuality that renders style a limiting

concept when approaching Spanish architecture of the seventeenth century. Yet, there

was a singular movement in the late eighteenth century to deride ornamented works of

architecture of the previous century on stylistic as well as ideological grounds. The

decline of Spanish power over the course of the seventeenth century is a leitmotif in

Eugenio Llaguno y Amirola’s manuscript for the Noticias de los arquitectos y

arquitectura de Espa

~

na. An Enlightenment-era scholar and politician, Llaguno began

drafting his ideas in the late 1760s and completed the manuscript of the Noticias by

1790.

8

He died nine years later and Juan Agust

ınCe

an Berm

udez took up the task of

editing Llaguno’s text some years after that, giving rise to complications about the

work’s authorship.

9

Llaguno and Ce

an both traveled in intellectual circles and both shared affinities with

the Enlightenment writer, statesman, and occasional architecture critic, Gaspar Melchor

de Jovellanos (1744–1811), who served as a mentor for the young Ce

an.

10

Jovellanos

found much to celebrate in Spain’s Gothic heritage, as well as in the neoclassical

restauraci

on brought about in the last decades of the eighteenth century. This

ideologically-charged restoration was the built evidence of the arrival of the

Enlightenment in Spain and symbolized for Jovellanos the rejection of the baroque or

what was then called the churrigueresco or estilo borrominesco—disparaging labels that

took aim at Churriguera and the Italian architect, Francesco Borromini (1599–1667).

6

Alfredo Vigo Trasancos, La fachada del Obradoiro de la Catedral de Santiago, 1738–1750: Arquitectura, triunfo y

apoteosis (Madrid: Electa, 1996).

7

Sacheverell Sitwell, Spanish Baroque Art with Buildings in Portugal, Mexico, and Other Colonies (London: Duckworth,

1931), 9.

8

Eugenio Llaguno y Amirola, Noticias de los arquitectos y arquitectura de Espa

~

na, ed. Juan Agust

ınCe

an Berm

udez, 4

vols. (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1829). A facsimile edition (Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando,

1977) includes brief biographies of Llaguno and Ce

an as well as an index by Luis Cervera Vera. On Llaguno, see

Miriam Cera Brea, Arquitectura e identidad nacional en la Espa

~

na de las Luces (Madrid: Sociedad Espa

~

nola de

Estudios del Siglo XVIII, 2019).

9

For Ce

an, see Elena Mar

ıa Santiago P

aez, ed. Ce

an Berm

udez: Historiador del arte y coleccionista ilustrado (Madrid:

Centro de Estudios Europa Hisp

anica and Biblioteca Nacional de Espa

~

na, 2016). Cera Brea, Arquitectura e identidad,

36–66, offers an overview of Ce

an’s contribution to the Noticias. See also Daniel Crespo Delgado and Miriam Cera

Brea, “Ce

an y la arquitectura,” in Santiago P

eaz, ed., Ce

an Berm

udez, 247–53.

10

For Jovellanos and architecture, see the introductory study to Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Memorias hist

orico-

art

ısticas de arquitectura, eds. Daniel Crespo Delgado and Joan Domenge i Mesquida (Madrid: Akal, 2013), 13–55.

Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Jer

onimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment (Albuquerque, NM:

University of New Mexico Press, 2017), and Janis Tomlinson, Goya: A Portrait of the Artist (Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 2020), offer important recent contributions to the study of the Spanish Enlightenment.

436 J. ESCOBAR

Volume 1 of the Noticias opens with an informative prologue written by C

ean. In the

opening lines, Ce

an records that Llaguno’s intended publication of the Noticias was first

announced by Jovellanos at a public event in January 1788. Ten years later, Ce

an was in

the process of publishing his Diccionario hist

orico de los profesores de las bellas artes en

Espa

~

na, an encyclopedia of biographies of Spanish artists that appeared in 1800 and

helped establish the modern discipline of art history in Spain.

11

In the midst of this

project, in 1798, Llaguno approached Ce

an asking him to include the biographies of

architects that he had written—namely, the draft Noticias—as part of the Diccionario

project. Although Ce

an declined, he inherited Llaguno’s manuscript, a copy of which

survives in New York, upon the elder author’s death in 1799.

12

Llaguno’s original text

spanned a millennium, beginning in the year 720 and ending in 1734, a decade prior to

the establishment of the Royal Academy in Madrid. When Ce

an turned to the

manuscript following the publication of his Diccionario, he sought to fill the lacunae he

found in Llaguno’s research and to bring the manuscript’s narrative up to date through

extensive new scholarship carried out by a team of archivists. In this way, C

ean was the

editor of the Noticias as well as de facto co-author.

For the prologue, Ce

an presents a sweeping history of Spanish architecture divided

into ten eras, a structure that reflects Llaguno’s original manuscript. From the

rudimentary contributions of the Phoenicians, Ce

an discusses Roman and early

medieval buildings with a surprising admiration for the contribution of Muslim

architects, providing an index of Arabic words still used in construction practice.

13

Following a consideration of the early Renaissance era, Ce

an declared the reign of

Philip II during the second half of the sixteenth century to have marked the arrival of

“purity and perfection” in Spanish architecture brought about by the initiation of

construction at the Escorial in 1563.

14

This sentiment, too, reflected Llaguno’s narrative. In the first volume of the Noticias,

Llaguno labeled the sixteenth century as the “happiest” era for Spanish architecture.

15

His lengthy discussion of Philip II’s Escorial—along with Ce

an’s formidable,

complementary research—appears in volume 2, where it is celebrated as the century’s

representative building. Significantly, the chronological parameters of volume 2

correspond to the lifetime of Juan de Herrera (ca. 1530–97), the Escorial’s chief designer

who emerges as the hero of the Noticias.

16

The impact of the Escorial on contemporary

11

Ce

an, Diccionario hist

orico; David Garc

ıaL

opez, “El Diccionario hist

orico de los m

as ilustres profesores de las bellas

artes en Espa

~

na,” in Santiago P

eaz, ed., Ce

an Berm

udez, 225–45.

12

Hispanic Society of America Library, New York HC 380/666 Llaguno. Cera Brea, Arquitectura e identidad, 35,

suggests the New York manuscript is a copy of Llaguno’s original.

13

The celebration of Spain’s Muslim past has been demonstrated by Jorge Ca

~

nizares-Esguerra, How to Write the

History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Stanford,

CA: Stanford University Press, 2001), 155–60, to be part of a patriotic campaign by Spanish Enlightenment

intellectuals.

14

Noticias, vol. 1, xxxvi: “Sin embargo de los grandes progresos que hizo entonces en Espa

~

na la arquitectura greco-

romana no lleg

o

a su pureza y perfeccion hasta el a

~

no de 1563, en que el gran Juan Bautista de Toledo traz

oel

suntuoso monasterio de S. Lorenzo del Escorial, y por mejor decir hasta que le aument

o y concluy

o su disc

ıpulo

Juan de Herrera.”

15

Noticias, vol. 1, 138: “el siglo XVI, el mas feliz para la arquitectura en Espa

~

na.”

16

For Herrera: Agust

ın Ruiz de Arcaute, Juan de Herrera: Arquitecto de Felipe II (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1936 [reissue

edition with introduction by Javier Ortega Vidal, Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, 1997]); and Catherine

Wilkinson-Zerner, Juan de Herrera: Architect to Philip II of Spain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993). On

Herrera’s significance in the Noticias, see Cera Brea, Arquitectura y identidad, 285–306.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 437

architectural practice is explored in most of volume 3 by whose end Llaguno denotes

the emergence of “bad taste” (mal gusto) in the 1630s.

17

In the opening pages of volume

4, Llaguno singles out Alonso Cano (1601–67), more famous as a painter today, as the

first true offender of architectural practice. The biographical entry offers little

information about Cano. Instead, it critiques the abilities of painters who turned to

architecture, pursuing novelty at the expense of rules established by the Greco-Roman

architect Vitruvius. Revealing an affinity with the Italian critic Francesco Milizia (1725–

98), Llaguno lays the blame for excessive invention on Borromini.

18

From Alonso

Cano’s errors, he regrets, “the delirious Borromini sect [was born. It] immediately

diffused itself in Spain and came to have a greater following than in its country of

origin, principally among painters and carvers.”

19

The architects who received Llaguno’s wrath were precisely those who were active in

the late decades of the seventeenth century and well into the eighteenth. Llaguno labeled

them heresiarcas, or heretics, and Ce

an embraced the term which both authors aimed at

designers who broke with their vision of what classical architecture should look like.

Jos

e Benito de Churriguera was an obvious target of Llaguno’s. Churriguera also

merited a long footnote by Ce

an, who criticized the Goyeneche Palace and its

“horrendous” portal that had been reformed for the Royal Academy. Other so-called

heretics included Francisco Hurtado Izquierdo (1669–1725), Narciso Tom

e (1690–

1742), and Pedro de Ribera (1681–1742), three builders whose biographies appear in a

single, brief entry.

20

Llaguno excoriated these architects for the “extravagances and

absurdities” he claimed were most readily visible on building portals, church retablos,

and what he calls adornos.

21

The last term is vague, but it implies a disdain for

ornament that informed academic debates in many European and Latin American cities

in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

22

Llaguno viewed the promise of salvation from architectural heresy in the restoration

of classical architecture in Spain. Yet, as noted already, he ended his narrative in the

year 1734. Thus, neoclassical reforms became the topic of a 120-page appendix that

Ce

an authored for the fourth volume of the Noticias. At the outset of this addendum,

Ce

an writes that he was encouraged to continue Llaguno’s work to his present day by

various academicians and “lovers of the fine arts.” These latter individuals would have

included readers of Ce

an’s Diccionario who were already familiar with the author’s

admiration of pedagogic reforms instituted by the Royal Academy. Ce

an’s appendix

opens with the arrival of the Italian architects Filippo Juvarra (1678–1736) and

Francesco Sabatini (1721–97) and continues with the successes of their Spanish pupils

Ventura Rodr

ıguez and the brothers Juan and Diego de Villanueva most importantly.

17

Noticias, vol. 3, 157. The phrase appears in the biography of architect Juan G

omez de Mora whose design for the

Jesuit College of Salamanca is cited as “introduciendo el mal gusto en la arquitectura.”

18

Francesco Milizia, Memorie degli architetti antichi e moderni (Parma: Stamperia Reale, 1781). On the reception of

Milizia’s book in Spain, see Cera Brea, Arquitectura e identidad,30–36.

19

Noticias, vol. 4, 40: “De aqu

ı naci

o la delirante secta borrominesca, que difundida inmediateamente en Espa

~

na

logr

o aun mayor s

equito que en el pa

ıs donde tuvo su or

ıgen, principalmente entre pintores y tallistas.”

20

Noticias, vol. 4, 102–07.

21

Noticias, vol. 4, 106.

22

For the case of Spain, see Sambricio, La arquitectura espa

~

nola. For Latin America, the essays in Paul B. Niell and

Stacie G. Widdifield, eds., Buen Gusto and Classicism in the Visual Culture of Latin America, 1780–1910

(Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2013), offer excellent comparative material.

438 J. ESCOBAR

Ce

an’s attention to Spanish-born heroes furthermore reveals the context in which he

wrote, namely the years following the Napoleonic occupation of Spain from 1808 to

1813. That event lies behind the author’s last words in the Noticias: “At the age of

eighty, I am satisfied to have achieved, amidst so much work and so many persecutions,

completion of this appendix and these Notices on the Architecture of Spain, which I

offer so that [Spanish design] might prosper in its advancement and recover the good

name and fame that it once had in the reign of Philip II.”

23

Thus, the political project to shape a new national identity found an outlet in the

history of Spanish architecture. For both Llaguno and Ce

an, the architectural style that

emerged in the seventeenth century could be equated with what they judged the

political failures of late Spanish Habsburg monarchs. In this curious case of myth

making, early Habsburg rulers such as Charles V and Philip II could be presented as

forward-looking, whereas those who ruled from 1598 to 1700 were blamed for Spain’s

downfall.

24

Oddly, both author and editor overlooked the early Bourbon monarchs who

ruled during the height of the careers of Churriguera, Ribera, and other maligned

architects. Instead, they praise the Bourbon rulers of their own era—beginning with

Ferdinand VI, founder of the Royal Academy—liberally at the expense of the

Habsburgs. The myth of Bourbon reforms is one that historians of the early modern

Spanish world are now actively dismantling, and that is another story.

25

With regard to

the history of architecture, Llaguno and Ce

an’s official history, sanctioned by the

Spanish royal press under Bourbon rule, reinforced a narrative of Habsburg decadence

that has resulted in an oversight of the seventeenth century still in need of correction.

The Formation of the Baroque in Spain

Llaguno and Ce

an’s Noticias remains to this day the basis for Spanish architectural

history. Although much of its content—especially Ce

an’s documentary research—

remains invaluable, its continued authority rests on its promotion as the definitive text

on the subject in the twentieth century. George Kubler employed its schema for his

contribution to the Pelican History of Art series published in 1959—the only existing

English-language survey of early modern architecture in Spain and its empire

26

—and

the Spanish Royal Academy of Fine Arts published a facsimile edition of the Noticias in

23

Noticias, vol. 4, 339–40: “No estoy menos satisfecho de haberlas servido en medio de muchos trabajos y

persecuciones con haber podido llegar a cabo de ochenta a

~

nos de edad, dando fin

a este Ap

endice y

a estas

Noticias de la Arquitectura en Espa

~

na, que les consagro para que prosperen en sus adelantamientos, y recuperen

el buen nombre y fama que tuvieron en el reinado de Felipe II.”

24

On myths of the failed Habsburg monarchy, see Ruth MacKay, “ Lazy Improvident People”: Myth and Reality in the

Writing of Spanish History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006); Henry Kamen, Imagining Spain: Historical

Myth & National Identity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008). See also Richard L. Kagan, Clio and the

Crown: The Politics of History in Medieval and Early Modern Spain (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press,

2009) on debates surrounding history-writing in the Habsburg era itself.

25

The effort in this regard is widespread, from a reinvigorated exploration of science to new examinations of

political history. On the latter topic, see Gabriel Paquette, Enlightenment, Governance, and Reform in Spain and Its

Empire, 1759–1808 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008); Kenneth Andrien and Allan Kuethe, The Spanish Atlantic

World in the Eighteenth Century: War and the Bourbon Reforms, 1713–1796 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2014).

26

George Kubler, “Part One: Architecture,” in George Kubler and Mart

ın Soria, Art and Architecture in Spain, Portugal

and Their American Dominions, 1500–1800, (Baltimore, MD: Penguin, 1959), 1–104.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 439

1977. Nineteenth-century reactions to Llaguno and Ce

an’s version of history, however,

were not uniformly positive.

A different view of early modern architecture was advanced in Jos

e Caveda’s Ensayo

hist

orico sobre los diversos g

eneros de Arquitectura empleados en Espa

~

na (Historical

essay on the diverse genres of Architecture employed in Spain) of 1848.

27

Caveda

organized his book chronologically, with what he called the estilo borrominesco serving

as the topic of the twenty-ninth of thirty chapters in total. Although he reveals a

neoclassical bias, Caveda considered Juan de Herrera’s architecture dry by what he

called “modern” standards. The Borromini style, defined by “ostentation and

playfulness in its ornament, delirium in its conceptions, refinement in its ingenuity,

[and] caprice and dangerous novelty in its forms,” was for Caveda complex and worthy

of admiration.

28

Evoking a Hegelian spirit to explain seventeenth-century trends,

Caveda equated architectural invention with the metaphor and hyperbole that could be

found in Spanish poetry of the age. Caveda astutely observed that earlier critics focused

almost exclusively on fac¸ade portals and church retablos, completely ignoring, for

instance, structural innovations. With this mention of structure and the implied

mathematical underpinnings of building in the seventeenth century, Caveda highlighted

a persistent gap in our knowledge of Spanish architecture. In the chapter’s conclusion,

Caveda wrote that historians ought to be able to appreciate admirable characteristics of

a building that coexist with ornamental forms that might be deemed “deformities.”

29

Caveda’s Ensayo hist

orico was translated into German and published in Stuttgart in

1858. It was edited by Franz Kugler, who was simultaneously overseeing the publication

of an encyclopedic history of European art.

30

Although Spaniards would build much of

their research in art history upon the foundations of German scholarship, the case of

early modern architecture in Spain suggests that Caveda’s writing led the way.

Moreover, the German edition of the Ensayo hist

orico coincided with an especially

fruitful moment for the study of seventeenth-century European art. Kugler was the

mentor of Cornelius Gurlitt, who in the 1880s would write some of the first serious

studies of what came to be called the Baroque, a term that supplanted the existing

rubric of “Jesuit style.”

31

Gurlitt was a practising architect. So too was his pupil, Otto

Schubert, who published Geschichte des Barock in Spanien (History of the Baroque in

Spain) in 1908. Schubert’s was the first book devoted to Spanish architecture of the

newly coined era and the eighth volume in a series devoted to the history of modern

architecture.

32

The intellectual context for Schubert’s book can be widened to include

Heinrich W

€

olfflin’s influential study of Italian art and style, Renaissance und Barock and

27

Jos

e Caveda, Ensayo hist

orico sobre los diversos g

eneros de arquitectura empleados en Espa

~

na desde la dominaci

on

romana hasta nuestros dias (Madrid: Santiago Saunaque, 1848).

28

Caveda, Ensayo hist

orico, 21: “Osad

ıa y travesura en el ornato, delirio en las concepciones, refinamiento en el

ingenio, capricho y peligrosa novedad en las formas.”

29

Caveda, Ensayo hist

orico, 498: “y que vituperando en el Churriguerismo cuanto repugna al buen gusto, respetar

an

tambien aquellos rasgos, que revelan el genio de sus numerosos secuaces, sin condenarle absolutamente como

una monstruosidad, en que solo se encuentran deformidades.”

30

Jos

e Caveda, Geschichte der Baukunst in Spanien, ed. Franz Kugler; trans. Paul Heyse (Stuttgart: Verlag van Ebner &

Seubert, 1858).

31

On Gurlitt, see Evonne Levy, Propaganda and the Jesuit Baroque (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004),

36–41.

32

Otto Schubert, Geschichte des Barock in Spanien, Volume 8 of Geschichte der Neueren Baukunst (Esslingen: Paul

Neff, 1908).

440 J. ESCOBAR

Karl Justi’s pioneering work on Diego Vel

azquez, both published in 1888.

33

Jonathan

Brown has argued that Justi’s book revived interest in the art of Spain and especially for

the promotion of a golden age.

34

Schubert’s book sought to do something similar for

Spanish architecture.

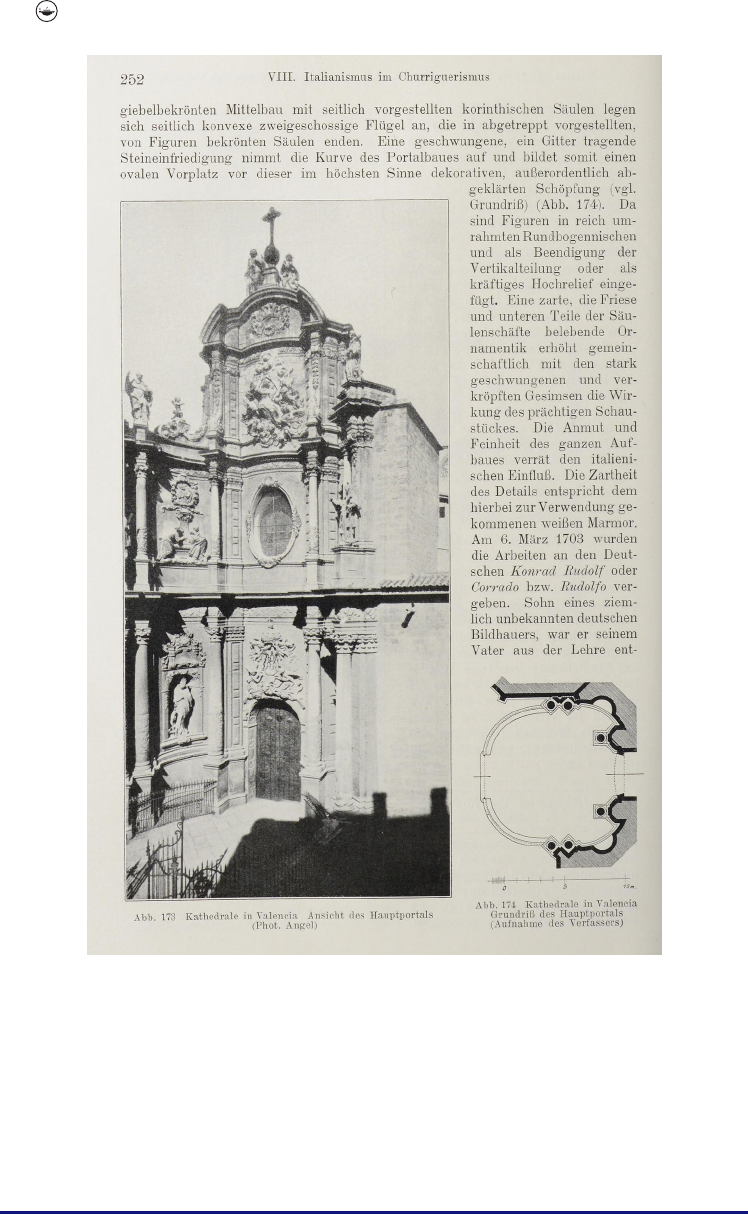

Like Caveda, Schubert adopted a measured outlook regarding ornament, although

his W

€

olfflin-inspired focus on style resulted in convoluted chapter titles and analyses.

The book’s 292 illustrations include photographs, plans, and section drawings, many of

which were based on measurements taken by the architect. An example is Schubert’s

plan of the south portal of Valencia Cathedral, which signals an effort to place the

creations of Spanish designers—or of foreigners working in Spain, as was the case with

the Valencia monument—within larger European traditions (Figure 4). The innovative

quality of the cathedral fac¸ade by Austrian architect Konrad Rudolf (d. 1732) speaks for

itself in a photograph, but its plan, isolated from the remainder of the building by

Schubert, allows a scholar to consider it in the tradition of Borromini and, thereby,

perhaps better understand the early nineteenth-century borrominesco label.

35

Nothing like Schubert’s book had appeared in Spain since Caveda’s work sixty years

earlier. The volume was translated into Spanish in 1924 and has remained a point of

reference in Spain ever since.

36

In a prologue to the 1924 edition, Manuel Hern

andez—

the translator about whom little is known—notes that Schubert’s primary achievement

was to gather data to help elucidate a little-known period. The book did not, according

to the translator, elaborate a systematic theory of aesthetic principles. That project of

defining the characteristics of baroque art and architecture was getting underway in

Spain in the 1920s, a time when art history was still a fledgling discipline. But, like

everything else in the country, it was disrupted by the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to

1939.

Following the devastation of war, reconstruction was the order of the day. Of great

consequence to the future history of the baroque, Franco’s government chose the age of

Philip II—the very era that Llaguno deemed Spain’s “happiest”—as a model for ministry

buildings, housing blocks, and cultural institutions sponsored by the modern state. Juan

de Herrera’s classical style had already been in vogue for large-scale public building

projects in Madrid in the 1920s.

37

Following Franco’s victory in 1939, however, even

Herrera’s work for Philip II to shape Madrid into a capital came to be equated with the

efforts of the twentieth-century dictator’s architects to modernize the city.

38

It was in this environment that George Kubler wrote a survey of seventeenth and

eighteenth-century Spanish architecture, which appeared in 1957 as part of the Ars

33

Heinrich W

€

olfllin, Renaissance und Barock: Eine Untersuchung

€

uber Wesen und Entstehung des Barockstils in Italien

(Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1888); Karl Justi, Diego Vel

azquez und sein Jahrhundert (Bonn: Friedrich Cohen, 1888).

34

Jonathan Brown, Images and Ideas in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Painting (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 1979), 3–18.

35

Joaqu

ınB

erchez, Arquitectura barroca valenciana (Valencia: Bancaixa, 1993), 78–87, offers a model interpretation of

Rudolf’s design within an expanded geographical framework.

36

Otto Schubert, Historia del Barroco en Espa

~

na, trans. Manuel Hern

andez Alcalde (Madrid: Saturnino Calleja, 1924).

37

Francisco Jos

e Portela Sandoval, “El eco del Escorial en la arquitectura espa

~

nola de los siglos XIX y XX,” in El

Monasterio del Escorial y la arquitectura (San Lorenzo del Escorial, 2002), 333–69.

38

This is the message promoted by Francisco

I

~

niguez Almech, who served as general commissioner for the

conservation of monuments following the Civil War and directed reconstruction efforts in Madrid; see

I

~

niguez

Almech, “Juan de Herrera y las reformas en el Madrid de Felipe II,” Revista de la Biblioteca, Archivo y Museo 19,

nos. 59–60 (1950): 3–108.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 441

Hispaniae series—the first modern encyclopaedic survey of Spanish art and

architecture—published by the Francoist press, Plus Ultra.

39

Kubler’s book came to

light in the context of the Spanish state’s effort to shape an official art history for Spain

and its former empire. That a scholar from the United States was invited to contribute

to the effort reveals an objective on the part of Spanish art historians to broaden the

Figure 4. Otto Schubert, photograph and plan of the south portal of Valencia Cathedral by Konrad

Rudolf, from Geschichte des Barock in Spanien (Esslingen: Paul Neff, 1908). Heidelberg University

Library, C6455-30, 252. Photo: Heidelberg University Library.

39

George Kubler, Arquitectura de los siglos XVII y XVIII, trans. Juan-Eduardo Cirlot (Madrid: Plus Ultra, 1957).

442 J. ESCOBAR

field of inquiry, something that Enrique Lafuente Ferrari and other Spanish scholars

would later admit had been greatly desired at the time.

40

In 1959, Kubler reworked this

text and expanded it to include the sixteenth century for his contribution to the

English-language Pelican History of Art series edited by Nikolaus Pevsner.

41

As with his

earlier Spanish-language survey, Kubler relied on Llaguno and Ce

an’s narrative arc for

this essay, even borrowing disparaging terms such as “heretical” to promulgate

orthodox classical prejudices. For English-language scholars, Kubler ’s earlier research

on architecture in colonial Latin America helped open a field of study. His work on

Spain, however, would have a very different effect owing to its reliance on biased,

Enlightenment-era scholarship.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, architectural history of the baroque in Spain

remained focused on regional studies with notable contributions on Andaluc

ıa,

Castile, and Galicia, a region whose seventeenth and eighteenth-century history was

ignored by Llaguno and Ce

an.

42

In scholarship published since the death of Franco

in 1975, a regionally focused approach to the baroque began to give way to an

investigation of Spanish design within a European context. Virginia Tovar Mart

ın’s

substantial writing on the Madrid architect Juan G

omez de Mora (1586–1648),

which sought to fill a void created by Llaguno and Ce

an’s cursory treatment of the

architect, is noteworthy although her local focus and overly determined effort to

elevate G

omez de Mora into a European architectural canon has softened the

potential impact of her scholarship.

43

General surveys of baroque art and

architecture from this period, including a six-volume encyclopaedia on the history

of Spanish architecture published in the mid-1980s, often reveal scholarly

limitations that existed in much of Spain owing to decades of an isolated academic

environment restrained by contemporary politics.

44

Since Spain’s entry into the European Union in 1986, Spanish scholars have further

integrated early modern Spanish art and architecture into international contexts. A

pivotal book in this regard has been Fernando Checa’s Felipe II: Mecenas de las artes,

which appeared in 1991 and restored the place of Philip II as a player on the European

Renaissance stage.

45

Checa went on to serve as director of the Museo Nacional del

40

See the introductory note in Enrique Lafuente Ferrari, “Bibliograf

ıa del profesor Enrique Lafuente Ferrari,” Academia

no. 59 (1984): 29–35.

41

Kubler, “Part One: Architecture.” For Pevsner’s scholarship, see Mathew Aitchison, “Pevsner’s Kunstgeographie: From

Leipzig’s Baroque to the Englishness of Modern English Architecture,” in Andrew Leach, John Macarthur, and

Maarten Delbeke, eds., The Baroque in Architectural Culture, 1880–1980 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 109–18.

42

For Galicia and Andaluc

ıa, see Antonio Bonet Correa, La arquitectura en Galicia durante el siglo XVII (Madrid:

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cient

ıficas, 1966 [reprint, Madrid, 1984]); idem, Art baroque en Andalousie,

trans. Jo

€

elle Guyot and Robert Marrast (Paris: Soci

et

e Franc¸aise du Livre, 1978). For Castile, see Virginia Tovar

Mart

ın, Arquitectos madrile

~

nos de la segunda mitad del siglo XVII (Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Madrile

~

nos, 1975);

idem, Arquitectura madrile

~

na del siglo XVII (Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Madrile

~

nos, 1983); Agust

ın Bustamante

Garc

ıa, La arquitectura clasicista del foco vallisoletano (1561–1640) (Valladolid: Instituci

on Cultural Simancas, 1983);

Fernando Mar

ıas, La arquitectura del Renacimiento en Toledo (1541–1631), 4 vols. (Madrid: Consejo Superior de

Investigaciones Cient

ıficas, 1983–85).

43

Virginia Tovar Mart

ın, Arquitectura madrile

~

na, op. cit.; Juan G

omez de Mora (1586–1648): Arquitecto y trazador del

rey y maestro mayor de obras de la Villa de Madrid (Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 1986).

44

The 1986 volume dedicated to the baroque is Jos

e Manuel Cruz Valdovinos Arquitectura barroca de los siglos XVII y

XVIII. Arquitectura de los Borbones. Aquitectura neocl

asica, Volume 4 of Historia de la arquitectura espa

~

nola, 6 vols.

(Barcelona: Planeta, 1986). Cruz’s bibliography includes the work of few foreign scholars beyond the Spanish-

language translations of Kubler and Schubert.

45

Checa, Felipe II: Mecenas de las artes (Madrid: Nerea, 1991).

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 443

Prado from 1996 to 2001, hiring curators who continue to promote an international

approach to the art of early modern Spain. An important example of Checa’s

contribution to an expanded view of baroque culture in Spain was the 1994 exhibition

and catalogue reconstructing the cultural milieu—although with only slight attention to

the architecture—of Madrid’s Royal Palace, a building lost to fire in 1734.

46

The effort

aimed to produce a “total history” of the palace, along the lines of Jonathan Brown and

John Elliott’s 1980 study of another lost Madrid monument, the Buen Retiro Palace.

47

Brown and Elliott’s admirable study persuasively situates the Spanish palace and its

collections within a European context yet remains limited on the topic of seventeenth-

century architectural history.

For over two decades, Fernando Mar

ıas, a contemporary of Checa’s and Spain’s

preeminent architectural historian, has called for a rethinking of the neoclassical

prejudice against Spanish baroque architecture.

48

One such appeal appeared in 1999 as

part of a volume produced alongside an exhibition of the work of Alonso Cano, the

artist identified by Llaguno as the corruptor of seventeenth-century architecture.

Building on analogies with literature that he employs in his study of the Spanish

Renaissance, Mar

ıas explored what he labeled the “eloquence” of the baroque style vis-

a-vis its critics. Moreover, he questioned the validity of relying on eighteenth and early-

nineteenth-century sources given their “Italo-centric conception” of what architecture

in Spain ought to look like. Although no blood was shed in writing this official history,

Mar

ıas concluded that “it has produced clear victors and losers in the [ … ] wars of

historiography.”

49

Spanish Habsburg Architects and Institutions

In a recent publication, I have suggested the term “Spanish Habsburg architecture”

might help recuperate a place for Spain in early modern architectural history.

50

For the

purposes of this essay, I maintain my focus on the seventeenth century and its oversight

given the extensive attention scholars have shown to eighteenth-century monuments as

representative of baroque architecture in Spain. Norberg-Schulz’s dismissal of Spanish

seventeenth-century buildings, for instance, was based on what he perceived to be a lack

of affinity in style with contemporary developments in Italy. The Italian bias was more

forceful in Anthony Blunt’s 1978 investigation of baroque architecture, which includes

only one substantial analysis of a seventeenth-century Spanish monument, Alonso

46

Fernando Checa, ed., El Real Alc

azar de Madrid: Dos siglos de arquitectura y coleccionismo en la Corte de los Reyes

de Espa

~

na (Madrid: Nerea, 1994).

47

Jonathan Brown and John H. Elliott, A Palace for a King: The Buen Retiro and the Court of Philip IV, revised and

expanded edition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003).

48

See especially Fernando Mar

ıas, “Elocuencia y laconismo: La arquitectura barroca espa

~

nola y sus historias,” in

Figuras e im

agenes del Barroco: Estudios sobre el barroco espa

~

nol y sobre la obra de Alonso Cano (Madrid:

Fundaci

on Argentaria, 1999), 87–112. Some of the ideas presented in this essay are reiterated in Fernando Mar

ıas,

“From Madrid to C

adiz: The Last Baroque Cathedral for the New Economic Capital of Spain,” in Henry Millon, ed.,

Circa 1700: Architecture in Europe, 1700–1800 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2006), 139–59.

49

Mar

ıas, “Elocuencia y laconismo,” 94: “Es posible, por tanto, que la visi

on de una arquitectura espa

~

nola

predominantemente ornamentalista est

e en deuda con una concepci

on italianoc

entrica y dieciochesca de la

historia de arquitectura moderna [ … ] habr

ıa producido claros vencedores y vencidos en el teatro de la guerra

historiogr

afica.”

50

Jes

us Escobar, “Architecture in the Age of the Spanish Habsburgs,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians

75, no. 3 (2016): 258–62.

444 J. ESCOBAR

Cano’s fac¸ade for Granada Cathedral. Blunt ’s consideration of Spain is otherwise

focused on the eighteenth century. Even the Granada Cathedral fac¸ade did not meet

Blunt’s criteria regarding style fully, as it reflected what he termed the “severity of

Herrera’s school” exemplified by the sixteenth-century Escorial.

51

With this statement,

Blunt ignored a long-held understanding in Spain about the impact of Philip II’s

monastery-palace on Spanish design. As an example, during a lecture honoring the

400th anniversary of the Escorial’s construction in 1963, the art historian Jos

e Cam

on

Aznar declared that the Escorial was “the foundation on which the baroque theatrical

machine would be built.”

52

Without the building, Cam

on continued, “Spanish baroque

architecture in and of itself does not make sense. [ … ] We can say that it varied from

architect to architect, but the Escorial—the most anti-Baroque monument par

excellence—always remained the essential schema.”

53

Cam

on’s words indicate a

willingness by Spanish scholars to embrace aesthetic contradictions, something

dismissed by Blunt, Norberg-Schulz, and Kubler who insisted that baroque design

arrived in Spain only in the eighteenth century.

The label Spanish Habsburg permits us to move the discussion of Spanish

architecture beyond debates over style and, among other things, take on Caveda’s

critique leveled in 1848 that too much attention is given to fac¸ades. Likewise, the term

allows us to focus on politics or, better, on the politics of architecture in early modern

Spain and its empire. Governance of the composite realm known as the Monarqu

ıa

Hisp

anica, or Spanish Monarchy, was a collective affair. This idiosyncratic grouping of

kingdoms and domains spread across the globe and was unified in the person of the

king—or, from 1665 to 1675, the queen regent—of Spain.

54

For the history of

architecture, the expansiveness of the realm demands thinking about seventeenth-

century monuments in cities as disperse as Brussels, Lima, Mexico City, or Naples

comparatively. Because architecture is a temporal art, historians must also tend to the

afterlives of Spanish Habsburg monuments. In this way, we must acknowledge the

destruction wrought upon seventeenth-century monuments owing to reforms led by the

Royal Academy as much as by natural disaster or warfare. Architectural projects were

also expensive undertakings in terms of monetary and human capital. Widening the

geographic scope and range of building types we study improves our vantage of the

seventeenth century. A consideration of fortifications and defensive structures that rose

along miles and miles of coastline, for instance, requires that we pay attention to

labor—free, indentured, and enslaved—that made this built empire possible.

Scholarship today is starting to do this important work, although, for the most part,

innovative research tends to focus on places far beyond the Iberian Peninsula. In what

follows, I illustrate two cases of seventeenth-century practitioners who were left out of

Llaguno and Ce

an’s official history but whose careers demonstrate that there remains a

good deal to learn about architecture in Spain itself. The first is Crist

obal de Aguilera (d.

1648), a builder usually considered a minor figure even though he worked in Madrid for

51

Anthony Blunt, Baroque & Rococo: Architecture & Decoration (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), 300.

52

Cam

on Aznar, La arquitectura barroca madrile

~

na (Madrid: Artes Gr

aficas Municipales, 1963), 4.

53

Cam

on Aznar, La arquitectura,4.

54

John H. Elliott, “A Europe of Composite Monarchies,” in Spain, Europe and the Wider World, 1500–1800 (New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 3–24.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 445

powerful institutions. Domingo Andrade (1639–1712), by contrast, was a major player

in the much smaller city of Santiago de Compostela. Although situated in the

northwestern periphery of the Iberian Peninsula, Andrade’s designs were affected by

cosmopolitan ideas and trends via his engagement with well-traveled patrons.

Most likely born in Madrid, Crist

obal de Aguilera was an expert builder and

waterworks engineer. In Madrid, the royal court, religious orders, and the municipality

alike erected buildings that promoted monarchical ideals. Aguilera worked for each of

these institutions.

55

Aguilera’s most consequential project was a building that survives

relatively intact: the Palacio de Santa Cruz, built originally as a courthouse and prison

under the jurisdiction of the Spanish court’s premier legislative body, the Council of

Castile (Figure 5). Begun in 1629 and completed eleven years later, the building was

known popularly as the C

arcel de Corte, or Court Prison.

56

Exemplifying trends in

seventeenth-century civic architecture in Castile, the building is framed by twin towers

and centered by a monumental portal adorned with classical ornament and royal

heraldry. The fac¸ade design has been said to recall the Escorial, leading to an assessment

of the building as derivative.

57

An examination of the building beyond its fac¸ade disposition suggests that it is little

like the Escorial. Its combination of building materials—brick, stone, iron, and slate—

reveals that Aguilera’s model was the south fac¸ade of Madrid’s Royal Palace, the most

Figure 5. Crist

obal de Aguilera, Palacio de Santa Cruz, formerly C

arcel de Corte, 1629–40, view of

the main fac¸ade with eighteenth-century reforms. Photo: Pablo Lin

es.

55

Aguilera’s biography is little studied. See Miguel Lasso de la Vega, “Arquitectos y alarifes madrile

~

nos del siglo

XVII,” Bolet

ın de la Sociedad Espa

~

nola de Excursiones 52 (1948), 161–221; Jes

us Escobar, Habsburg Madrid:

Architecture and the Spanish Monarchy (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2022), 104–05.

56

For the building, see Conde de Altea, Historia del Palacio de Santa Cruz, 1629–1950 (Madrid: n.p., 1949); Tovar

Mart

ın, Juan G

omez de Mora 130–34; Escobar, Habsburg Madrid,93–133.

57

Virginia Tovar Mart

ın, “Lo escurialense en la arquitectura madrile

~

na del siglo XVII,” in El Monasterio del Escorial y la

arquitectura, eds. Francisco Javier Campos and Fern

andez de Sevilla (San Lorenzo de El Escorial: Estudios

Superiores del Escorial, 2002), 285–311.

446 J. ESCOBAR

important built symbol of Spanish Habsburg power in the capital city. Beyond

correspondences with the fac¸ade, Aguilera’s plan for the Court Prison idealizes that of

the Royal Palace, creating a model for government architecture that would even inspire

design competitions for town halls and jails taught at the eighteenth-century Royal

Academy.

Because it was lost to fire in 1734, the Spanish Habsburg Royal Palace has been

forgotten by all but a few scholars who have pondered its architectural design.

58

From

1611 to 1630, in response to the Escorial but also in dialogue with a new Palazzo Reale

in the Viceroyalty of Naples, the main fac¸ade of Madrid’ s Royal Palace was reworked

primarily in stone although a tower dating to the 1560s built of brick and stone and

adorned with iron balconies and a slate-covered steeple was retained.

59

That tower was

associated with the era of Philip II, something Aguilera’s conciliar patrons also desired

for their new seat to judge by the Court Prison’s exterior appearance. For previous

scholars, the royal association has led to debates about authorship of the Court Prison,

with some seeking to assign credit to Juan G

omez de Mora, a prolific royal architect,

and others such as Schubert pointing to a Roman nobleman and master of the Royal

Works, Giovanni Battista Crescenzi (1577–1635), as designer. The documentary record

proves Aguilera’s authorship beyond a doubt. His absence from the foundational book

of Spanish architectural history has been enough, nonetheless, for scholars to speculate

otherwise.

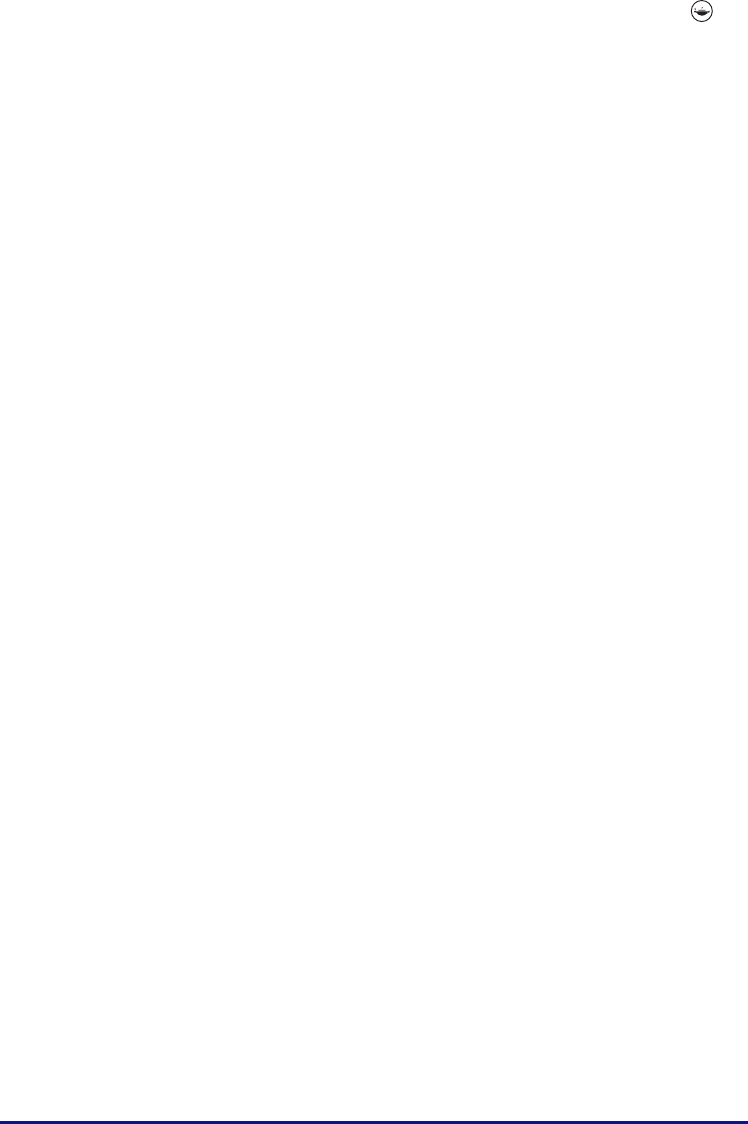

The judges officiating at the new Court Prison previously worked in tribunals located

in the Royal Palace whose plan, as noted, inspired their new building. Otto Schubert

included a plan of the Court Prison in his 1908 book which appeared also in the 1924

Spanish edition. The plan was not his own, but rather one made by a Spanish

government agency that reflected the building’s use in the 1890s as a foreign ministry.

In every subsequent study of the Court Prison, scholars have reproduced the same plan

without apparently visiting the building thereby limiting our understanding of its

original design. My recent book on seventeenth-century architecture in Madrid includes

a plan of the building in the year 1640 with which I reconstruct the uses of interior

spaces based on archival and site research, in addition to wide-ranging comparisons

informed by my interest in Spanish Habsburg governance (Figure 6).

60

Archival

documents allow me to hypothesize the location of a principal tribunal labeled B5 along

the building’s west flank, as well as an adjacent holding cell (B6) for which material and

archival evidence survives although it had gone unnoticed. Written descriptions and

rare drawings of tribunals and jails from Toledo to Mexico City help secure other data

that allow us to imagine people moving in and around this building as well as others

with similar institutional functions.

Aguilera toiled in the competitive artistic environment of the court yet that was not

enough for him to be remembered by Llaguno or Ce

an. Another disregarded figure was

Domingo de Andrade, a prolific designer who served as master builder at the Cathedral

58

Jose Manuel Barbeito, El Alc

azar de Madrid (Madrid: Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid, 1992); Barbeito,

“Vel

azquez y las obras reales,” in Checa, ed., El Real Alc

azar,80–95; Escobar, Habsburg Madrid,47–91. Llaguno and

Ce

an include one sentence about the building in their biography of G

omez de Mora; Noticias, vol. 3, 156.

59

On the Naples connection: Sabina De Cavi, Architecture and Royal Presence: Domenico and Giulio Cesare Fontana in

Spanish Naples (1592–1627) (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 193–212.

60

Escobar, Habsburg Madrid, 110.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 447

of Santiago de Compostela from 1676 until 1700, the final quarter century of Spanish

Habsburg rule.

61

Despite his illustrious career and evidence of intellectual pursuits—in

1695, he authored a brief treatise on The Excellence, Antiquity, and Nobility of

Architecture

62

—Andrade, too, does not make an appearance in the Noticias. In his

practice, Andrade adhered to principles of classical architecture learned from treatises

and he applied these tenets to local Romanesque and Gothic buildings that he often

adapted. Andrade also gained an awareness of trends far from his base in Santiago by

working for patrons who had first-hand experience of distant places and buildings.

Famous as a destination for medieval pilgrimage, Santiago de Compostela underwent a

period of architectural renovation in the late seventeenth century with Andrade designing

some of its most significant monuments. These include the Royal Portal located at the

cathedral’s southeast corner and fronting the Plaza de la Quintana (Figure 7). The portal

fronts a series of improvements to the cathedral’s interior including a new sacristy and a

sequence of hallways Andrade designed for circulation as well as ceremony. Andrade’s

portal composition takes its cue from contemporary palace design in Italy and Spain, as

well as the Spanish American viceroyalties, with a three-story frontispiece serving as its

anchor. Four colossal half columns in the Doric Order rest atop plinths and mark the

three central bays. In the centermost bay, wooden doors open to the cathedral interior

with the Spanish Habsburg arms carved in high relief in a blind aedicule directly above. A

Figure 6. Plan of the C

arcel de Corte in 1640. Drawing by Chris Phillips.

61

The ground-breaking study is the dissertation by Miguel Ta

ın Guzm

an, Domingo de Andrade, maestro de obras de

la Catedral de Santiago (1639–1712), 2 vols. (La Coru

~

na: Edicios Do Castro, 1998). See also Bonet Correa, La

arquitectura en Galicia.

62

Domingo de Andrade, Excelencias, antiguedad, y nobleza de la arquitectura (Santiago de Compostela: Antonio Frayz,

1695). For a facsimile, see Ta

ın Guzm

an, Domingo de Andrade, vol. 2, 815–64.

448 J. ESCOBAR

statue of the cathedral’s patron saint once crowned the portal’s third level. Completed in

1700, the Royal Portal was one of the last monuments built during the reign of the

Spanish Habsburgs. It was first given notable consideration by Antonio Bonet Correa in a

1960 study dedicated to baroque architecture in Galicia, yet Andrade remained a

provincial figure in the historiography of Spanish architecture until the publication of

Miguel Ta

ınGuzm

an’s dissertation on the builder in 1998.

Patronage of the Royal Portal, too, has gone largely unremarked until recently. Yet,

this aspect of the building offers a compelling reason to reexamine this monument

within the context of the Spanish Habsburg global, transnational realm. The fac¸ade was

commissioned and funded by the Mexican-born archbishop of Santiago, Antonio de

Monroy (1634–1715) whose arms appear to the immediate left of the main entrance.

63

Prior to arriving in Santiago in 1678 to take up his post, Monroy had been a prominent

cleric and intellectual in Mexico. Among his accomplishments, he officiated at funerary

ceremonies for King Philip IV of Spain in Mexico City in 1666, the same year he was

named rector of the Dominican College of Porta Coeli. In 1674, Monroy was sent to

Rome where two years later he was named Master General, or worldwide leader, of

the Dominican Order, a post he held for nine years before being called to Spain.

As archbishop of Santiago de Compostela, Monroy became a major patron of

Figure 7. Domingo de Andrade, P

ortico Real de la Quintana, Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela,

1696–1700. Photo by author.

63

For Monroy, see Ta

ın Guzm

an, Domingo de Andrade, vol. 1, 24; Jes

us Escobar, “Baroque Spain: Architecture and

Urbanism for a Universal Monarchy,” in Renaissance and Baroque Architecture, ed. Alina Payne (Oxford: Wiley-

Blackwell, 2017), 669–72.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 449

architecture and helped fund projects in town and at the cathedral, including Andrade’s

Royal Portal. Thus, one of the last monuments of the Spanish Habsburg era was

sponsored by an American-born imperial subject and designed by an architect missing

from the first history of Spanish architecture. In the 1730s, Andrade’s Royal Portal

would inspire Fernando de Casas’s design for the second tier of the spectacular

Obraidoiro fac¸ade of the Cathedral of Santiago mentioned already. Just as that

eighteenth-century fac¸ade disguised the building’s original Romanesque front, one

could argue that Llaguno and Ce

an’s history of Spanish architecture—which ignored

post-medieval interventions at the building altogether

64

—helped conceal a fuller

understanding of its seventeenth-century origins.

Conclusion

These brief words about projects designed by Crist

obal de Aguilera and Domingo de

Andrade illustrate the significance of institutions and individuals in giving shape to

architecture and monuments in the early modern Spanish Monarchy. For example,

Aguilera’s seventeenth-century Court Prison employed materials and design principles

that linked it visually to the Royal Palace and, thus, to the authority of the Habsburg

monarchy, but at the same time, would appeal to Bourbon-era proponents of

neoclassicism at the Royal Academy. In the case of Andrade’s Royal Portal, the patronage

of an archbishop whose ideas about monumental architecture were formulated in Mexico

City and Rome illustrates the dynamic transfer of aesthetic principles across the Atlantic

Ocean. Both cases demonstrate one of the most promising outcomes in rethinking our

conception of Spanish baroque architecture: the recuperation of buildings and builders

left behind in the historiography. The Enlightenment view of seventeenth-century Spain

as a place in which nothing of importance was built by a monarchy in political decline

can no longer stand. The Spanish Empire was a powerful force in the early modern global

world. Its architecture provides a wealth of primary source material for the study of the

institutions and individuals that animated it.

Acknowledgments

This essay is dedicated to John Pinto. For helpful comments of this work in progress, I wish

to thank gracious audiences at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; the

Department of Art & Archaeology, Princeton University; and the Kunsthistorisches Institut,

Florence. I also received generous feedback from participants at an Aggregrate workshop held

at Northwestern University. I owe special thanks to friends who read earlier drafts and

provided exceptional advice: James Amelang, Thadeus Dowad, Richard Kagan, Ayala Levin,

Felipe Pereda, Michael Schreffler, Amanda Wunder, and the late Jonathan Brown. Lastly, I am

grateful to the two anonymous peer reviewers and to editors Charlotte Byrne, Mark

McDonald, and Sarah Symmons.

64

Noticias, vol. 1, 31–32, offers a brief entry about the Romanesque building mentioning a sixteenth-century cloister

and other “sumptuous” additions in passing. In the few words about Fernando de Casas that appear in the

Noticias (vol. 4, 115), Llaguno and Ce

an ignore his work at Santiago de Compostela.

450 J. ESCOBAR

Disclosure Statement

The author has not declared any potential conflict of interest.

Notes on Contributor

Jes

us Escobar is Professor of Art History at Northwestern University and a specialist in the

architecture and urbanism of the early modern Spanish Empire. His research focuses on

cultural and political exchanges among institutions and individuals with special attention to

the circulation of architectural knowledge in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth

centuries. Escobar is also editor of the scholarly book series, Buildings, Landscapes, and

Societies. His latest book, Habsburg Madrid: Architecture and the Spanish Monarchy, was

published by Penn State University Press in 2022.

HISPANIC RESEARCH JOURNAL 451